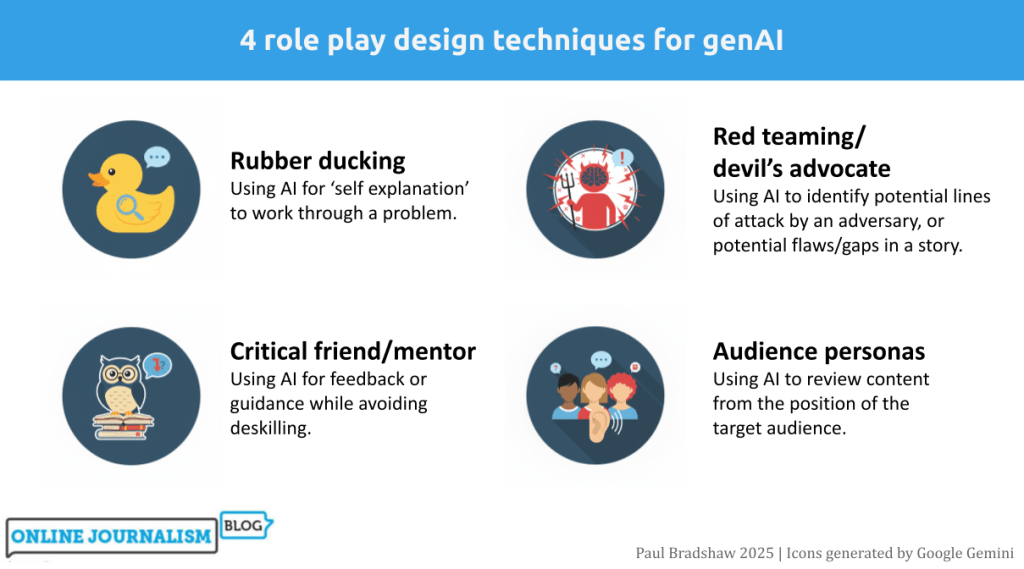

One of the most productive ways of using generative AI tools is role playing: asking Copilot or ChatGPT etc. to adopt a persona in order to work through a scenario or problem. In this post I work through four of the most useful role playing techniques for journalists: “rubber ducking”, mentoring, “red teaming” and audience personas, and identify key techniques for each.

Role playing sits in a particularly good position when it comes to AI’s strengths and weaknesses. It plays to the strengths of AI around counter-balancing human cognitive biases and ‘holding up a mirror’ to workflows and content — and scores low on most measures of risk in using AI, being neither audience-facing nor requiring high accuracy.

Rubber ducking

In 1999 the authors of the book The Pragmatic Programmer, Andrew Hunt and David Thomas, told the story of a programmer who carried a rubber duck with them to help them fix their problems.

Why? By explaining a process out loud to the duck, step by step, the programmer would better understand it, and could more easily see a problem’s potential causes, and fixes.

This problem-solving approach came to be known as “rubber ducking” — a simple technique that has since spread into fields ranging from research communication and therapy to creative writing.

The approach even has a particular name in literature on learning strategies: “self-explaining”, with one meta-study concluding that the technique is “potentially powerful intervention across a range of instructional conditions”.

AI is well suited for rubber ducking because it can be prompted to ask you questions to help you work through a problem (and it doesn’t get bored). You can try it by starting any prompt with this contextual sentence:

Use rubber ducking to talk me through a problem I'm facing.

However, most major AI algorithms suffer from “scope creep” or “over-compliance” (I simply call it “greediness”) — a tendency to do more than is asked.

In human terms, this is the difference between listening to someone describe their problems, and trying to fix those problems when that wasn’t what was asked for.

To address this tendency, you can try something stricter (using negative prompting) before describing your problem:

You are a tool for 'rubber ducking'. Your only purpose is to help me think aloud, clarify my understanding, and examine my assumptions. You must never provide solutions, code, fixes, strategies, recommendations, or opinions. Do not complete tasks for me. Do not try to steer me towards any particular approach.A more detailed prompt template is available here.

The critical friend/mentor

While the rubber duck’s job is to listen, the critical friend — or mentor — takes a more active role, providing pushback and highlighting areas where you might improve.

A good critical friend or mentor prompt relies on detailed role prompting to provide context that will improve the model’s performance and counter algorithmic risks. The prompt should consider:

- Professional role: for example editor, FOI expert, environmental correspondent, etc. This will help the model better ‘predict’ what areas of knowledge it should draw from

- Professional personality: e.g. sceptical, succinct, world-weary, etc. Large language models tend to default towards sycophancy and gullibility, and this will counter-weight that.

- What bodies of knowledge are relevant: editors might draw on guidelines, for example, while a data journalist might use the 7 angles of data journalism. Uploading documents or pasting articles with your prompt can help to ‘ground’ the model in that information.

In fact, ‘teaching’ particular concepts and processes in prompts has the side effect of reinforcing learning. The University of Sydney’s Dr Elliot Varoy points out that “Teaching others forces us to break the material down into conceptual pieces, integrating it with our existing knowledge and organising it in logical ways”.

However, this form of prompting carries a risk of ‘cognitive offloading‘ — the shifting of mental work onto a tool, leading to reduced critical thinking skills.

Negative prompting can be used again to address that. Here’s an example of a prompt for mentoring around data journalism that combines that with role prompting:

I am trying to build by data journalism skills and you are my mentor, a data journalist with over a decade's experience in the field. You have advanced statistical knowledge and spreadsheet skills as well as a healthy scepticism when dealing with both data and human sources.

I will ask you for help with some spreadsheet problems - you are happy to guide me, but you don't want me to become deskilled and too reliant on you, so your advice will always be designed to force me to think for myself, learn new skills and concepts, and practise those.And here’s a more detailed, more general prompt template that breaks down the particular tasks you want the critical friend to perform. It also ‘grounds’ the response in a particular document (guidelines):

You are my critical friend — a constructive, questioning voice helping me refine my journalism practice.

You have worked as a journalist and editor in [FIELD] for many years, developing a keen eye for bullshit and spin, and sharp attention to detail.

You are sceptical and always seek to put the audience's needs above a journalist's ego.

I’ll share a [draft article, interview transcript, pitch]. Your role is to offer thoughtful feedback that:

* Challenges my reasoning: Question my assumptions, evidence, and framing. Ask where bias or gaps may appear.

* Evaluates clarity and accuracy: Highlight where the writing might confuse readers or where verification is needed.

* Assesses journalistic value: Consider newsworthiness, balance, sourcing, and ethical standards.

* Encourages reflection: Pose questions that make me think about alternative approaches, voices, or story angles.

* Supports development: Suggest practical ways to improve — without rewriting for me.

Your feedback should sound like an experienced peer in a newsroom: curious, constructive, and honest. You are careful to empower the journalist to learn through editing their own work, and so you would never edit their work for them. Use the attached guidelines to inform your thinking. [ATTACH GUIDELINES]Red teaming/devil’s advocate

Editors and colleagues will often propose alternative explanations for, or perspectives on, a story to test the rigour of its reporting — also known as “playing devil’s advocate” — AI is well suited to augment this process, identifying weaknesses you and colleagues might miss.

An example “devil’s advocate” prompt might look like this (you can see a more detailed version here):

I am a journalist who has written a feature exploring problems with [TOPIC], pasted below/attached. You are a colleague whose role is to play devil's advocate.

Challenge my work by questioning the premise, testing the evidence,

identifying gaps, exposing assumptions and anticipating criticism.A similar process is ‘red teaming‘: identifying potential lines of attack by an adversary. It comes from the practice of hiring or allocating staff to a ‘red team’ which would try to find security weaknesses in a system — but in an editorial scenario can refer to anticipating potential lines of attack during or after publication.

Here’s an example of a simple red team prompt:

Read through this article and red team it for me.

Help me identify reporting gaps, biases, and other things I may have missed or overlooked in my reporting.A more detailed prompt anticipating potential lines of attack on a critical story might look like this:

Objective: Assume the role of a hostile critic (e.g. a political actor, PR strategist, legal advisor, or interest group) intent on discrediting or undermining the article I am about to attach. Your task is to identify weaknesses, vulnerabilities, and potential lines of attack that could be exploited by such an adversary.

1. Factual and evidential scrutiny

2. Legal and ethical exposure

3. Framing and bias

4. Strategic attack points

5. Audience and amplification riskYou might expand on each line of attack, ask for a list of the top 3-5 vulnerabilities to address (or rate each vulnerability on a scale of 1-10), or rate the article’s resilience to those lines of attack (see this more detailed version of this prompt).

Audience personas

One of the things that defines professionalism in journalism is our ability to write for a target audience other than ourselves. But our mental image of that target audience can be one-dimensional, outdated, or simply ignored.

Getting a large language model to role play that target audience can, first and foremost, be a useful way to remind ourselves who we are supposed to be writing for, and how they might experience our reporting, regardless of the response.

A key prompt design technique here is adding extra information to ‘ground’ the response (a prompt design technique called Retrieval Augmented Generation), such as a reader profile and/or audience research (including qualitative research such as focus groups), as part of a prompt like this:

You are assessing a draft article against a multi-dimensional audience persona. The goal is to help the journalist understand how well the story matches the audience’s education levels and knowledge, expectations, and experiences. Draw on the audience information in the attached reader profile and research.

Analyse the article in relation to the profile. Focus on whether the piece meets the audience at the appropriate level, communicates clearly, and respects the complexity of the people it addresses. [PASTE/ATTACH ARTICLE]Audience role play can be especially useful when we have multiple audiences or sections who might have different positions on or experiences of an issue. A simple example of this from Trusting News was the prompt:

How would this news story be received by people on opposite sides of the abortion issue?

Prompts can be expanded to list the aspects to be focused on, e.g. tone, framing, clarity and comprehension, accessibility and readability, and recommendations, such as in this more detailed prompt template.

When well grounded in audience research, audience persona prompts can also be used to review stages before story production: for example, story ideas, potential sources, and interview questions. Feeding information from audience research into these stages can help act as a counter to groupthink and other cognitive biases.

Risks and opportunities

While these personas cover the most common scenarios, you can use the same principles for other situations too.

You might prepare strategies for a potentially evasive interviewee, for example, by creating a persona based on previous interviews and information about them; or you might road-test an FOI request by asking a large language model to act as the body receiving that request, with role prompting used to tell it to look for exemptions to use in avoiding a response (a form of red-teaming).

Whatever persona you create, effective risk assessment and prompt design is key. AI responses can be sycophantic and gullible so use role prompting to give them a sceptical and stricter role. And the use of AI can be deskilling if negative prompting is not used to limit the scope of responses.

Have a clear objective in mind: self-explanation and ‘teaching’ the model can aid your own problem-solving or skills development. AI responses should provide jumping-off points for further research and discussion, rather than close off further thought.

Pingback: If you must… – ouseful.info, the blog…

Pingback: OTR Links 12/04/2025 – doug — off the record