I’ve now covered almost all of the 5 roles in an investigations team I posted about earlier this year – apart from the multimedia journalist role. So here’s how to get started in that role.

Multimedia journalism is a pretty nebulous term. As a result, in my experience, when students try to adopt the role two main problems recur: 1) having a narrow assumption of what multimedia means (i.e. video) and 2) not being able to see the multimedia possibilities of your work.

Multimedia journalism is a very different beast to broadcast journalism. In broadcast journalism your role was comparatively simple: you had one medium to use, and a well-worn format to employ.

Put another way: in broadcast journalism the medium was imposed on the story; in multimedia journalism, the story imposes the medium.

Multimedia also has to deal with the style challenge I’ve written about previously:

“Not only must they be able to adapt their style for different types of reporting; not only must they be able to adapt for different brands; not only must they be able to adapt their style within different brands across multiple media; but they must also be able to adapt their style within a single medium, across multiple platforms: Twitter, Facebook, blogs, Flickr, YouTube, or anywhere else that their audiences gather.”

With that in mind, then, here are 4 steps to get started in multimedia journalism:

Step 1: Look for multimedia opportunities in your journalism

The style challenge outlined above means starting from a position of having to decide what medium to use – and the type of multimedia which is produced in this role will depend largely on the nature of the stories and investigations being pursued. Here are some typical examples of where multimedia can bring an extra dimension to a story:

- Case studies: video or audio interviews with someone at the heart of the story: affected by the issue or working at the coalface

- Reaction: video or audio interview with the person responsible: capturing their attempts to explain their role

- Clarity: charts, maps or infographic turning data into something that users can understand more quickly. Tools useful here include Google Charts and Gadgets (in Google Docs), Many Eyes and Tableau for charts; Tagxedo, Wordle or Many Eyes for word clouds; Google Maps and BatchGeo for maps; and Infogr.am for infographics.

- Explanation: taking something complex and making it accessible to a wider audience – this might be done through a graphic, or through a video or audio interview with an expert who can explain it clearly – including a member of the team

- Conflict and chemistry: staging a podcast discussion to flesh out the key themes in the issue being explored. This can be done in an entertaining way if your presenters have chemistry, or it can be done in an engaging way if you have two camps in conflict (make sure you can add clarity and expertise into the noise)

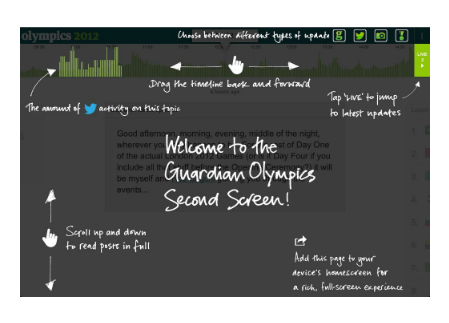

- Interactivity: producing something that users can interact with. Freedive is a useful tool for doing this with spreadsheets. There are also timeline tools like Dipity and Meograph, and charts and maps can be interactive too.

- Curation: bringing together multimedia content by users in a way that adds value

The multimedia journalist needs to be able to spot those opportunities for multimedia to play a role – and develop the skills to see them through. Here are some questions to ask:

- Does the story involve complex concepts that might be better illustrated through visual or aural means?

- Does the story require a response from someone, or a description of an event, where non-verbal cues such as their tone of voice or facial expression may be key?

- Are there different positions which would suit a discussion to flesh them out?

- Is there so much information involved that users might want to explore it themselves to pull out the bits directly relevant to them?

- Does the story involve figures or data that work better visually than in text?

- Is there user generated content related to the issue – online or in offline archives, or individuals’ possession – which could be brought together and highlighted?

Looking at plenty of examples of online multimedia is very important here. For the reasons explained above, broadcast journalism is not always the best example to follow. Look at David McCandless’s visualisation work or the discussions about best practice on Flowing Data. Look at the video work of Travis Fox and Michael Rosenblum’s students. Watch The Guardian’s video and the documentary channel on Vimeo. Listen to the most popular podcasts and micropodcasts; soak in audio slideshows – and ask yourself what makes them so effective.

The technical quality – and I know people will disagree with this – can wait.

Step 2: Plan and practise

The reason that I place technical skills second here is this: if you don’t have a story to tell, you are going to have neither the means nor the motive to develop your technical skills.

Furthermore, because there are now so many technical options available to the journalist, learning them all before going out to report is not the most efficient option.

So: story first, technicalities second.

Once you have a story, you have to decide how best to tell it. If it’s video, you will need to learn that. If maps, then look at that.

Don’t wait for someone to show you how: there are thousands of resources online to get you started, from Vimeo’s Video School and YouTube’s Playbook to the BBC College’s resources andMindy McAdams’s collection on audio and video production.

YouTube has tons of tutorials on pretty much any skill you might want to tackle, but there are also text resources such as The Society of Professional Journalists’ Digital Media Handbook Part 1 (PDF) and Part 2 which cover mapping and data visualisation, among other useful techniques, and the Knight Digital Media Center’s extensive tutorials.

For photography there’s this free book on DSLR Cinematography, while videographers can choose between this ebook (PDF) by Adam Westbrook on multimedia production and ImageJunkies’s free ebook on news and documentary filmmaking.

If you’re struggling for a reason to use multimedia, liveblogging is a particularly good opportunity to practise your skills: when there’s lots going on, what are the multimedia opportunities:

- Do you need to be in position for when something visually or aurally striking happens?

- Or do you need to interview the people taking part, for colour?

- Do you capture the atmosphere somehow?

- Do you map it?

- Do you attempt to flesh out rumours with some actuality?

Every choice counts – be prepared to make a lot of wrong ones, or at least to accept that part of the journalist’s job is deciding what to leave out.

Your first attempts will be crude and frustrating – but they will point you to the key issues, and provide the motivation for learning the techniques.

For example, your video may have poor audio, or be too shaky. There may be too much of you in it. Your map may have too little information. Your audio drones on for too long, then sputters out.

Largely this is about planning: checking out the location and picking a place where background audio isn’t too loud. Briefing the interviewee and getting in close. Researching your subject and knowing the right questions to ask – and when not to accept an answer.

So practise. Learn how to edit your work, just as you would edit your words. Learn how to film closely, or with a microphone, or both to get clearer sound. Learn how to kick off and wrap up audio succinctly. Practise.

Step 3: Improve the technical side with an understanding of principles

An understanding of key principles is just as important as technical ability: you need to understand what works well in a chosen medium: being able to hold a camera is worthless if you point it at something dull. Being able to edit audio isn’t going to help if you don’t ask the right questions in the interview. As countless examples of citizen journalism have proved: people will forgive poor technical quality if the newsworthiness of the content is strong enough. Here are some key principles that come to mind – I’d welcome others:

- Narrative: how to start, maintain interest, and end well.

- Interviewing: what questions to ask, when and how.

- Editing and composition: how to combine elements for maximum clarity and effect. Being ruthless in taking things out.

- Visual design: how to compose an image for impact, or what is most effective in a chart

Just as the story provides a focus for the development of technical skills, so these core principles should refine those further. In particular, they should help you make choices quickly, including the difficult ones. What to start with and what to end with. When and what to cut away. How to be confident in what you’re doing, and push for the right result.

Step 4: Start simple, and go from there

With those three steps established, there may be a temptation to try something with multiple angles, cuts, sections, or layers. So the final step is to step back, and start simple.

Mobile video is a good discipline here: it prevents you from using cutaways and other techniques to disguise your content – and forces you to focus on core qualities: clear audio, good questions, and an engaging subject.

Maps and charts should focus on a few key data points, and link to the rest.

A short podcast, tightly edited, will develop your production skills much better than a flabby multi-section programme which pulls you in too many different directions.

If you’re already good at photography, an audio slideshow will stretch you a little further. Master one part, and then build on that.

Comments especially welcome