The BBC College of Journalism asked me to revisit my Model for the 21st Century Newsroom 4 years on. You can now read the first part of the results on their blog – with further substantial parts to follow next week. Thoughts welcome.

Tag Archives: 21st century newsroom

20 free ebooks on journalism (for your Xmas Kindle) {updated to 65}

As many readers of this blog will have received a Kindle for Christmas I thought I should share my list of the free ebooks that I recommend stocking up on.

Online journalism and multimedia ebooks

Starting with more general books, Mark Briggs‘s book Journalism 2.0 (PDF*) is a few years old but still provides a good overview of online journalism to have by your side. Mindy McAdams‘s 42-page Reporter’s Guide to Multimedia Proficiency (PDF) adds some more on that front, and Adam Westbrook‘s Ideas on Digital Storytelling and Publishing (PDF) provides a larger focus on narrative, editing and other elements.

After the first version of this post, MA Online Journalism student Franzi Baehrle suggested this free book on DSLR Cinematography, as well as Adam Westbrook on multimedia production (PDF). And Guy Degen recommends the free ebook on news and documentary filmmaking from ImageJunkies.com.

The Participatory Documentary Cookbook [PDF] is another free resource on using social media in documentaries.

A free ebook on blogging can be downloaded from Guardian Students when you register with the site, and Swedish Radio have produced this guide to Social Media for Journalists (in English).

The Traffic Factories is an ebook that explores how a number of prominent US news organisations use metrics, and Chartbeat’s role in that. You can download it in mobi, PDF or epub format here.

A model for the 21st century newsroom (Thai Translation)

Joining the Spanish and Russian translations of the Model for a 21st Century Newsroom is this version in Thai. Many thanks to Sakulsri Srisaracam:

(แปลเป็นภาษาไทยโดยอ.สกุลศรี ศรีสารคามจาก Blog onlinejournalismblog.com ของ Paul Bradshaw)

ธรรมชาติของสื่อออนไลน์ที่สำคัญคือ มีความเร็ว (Speed) นักข่าวสามารถเผยแพร่ รายงานข่าวผ่านเครื่องมือบนอินเตอร์เน็ตและเทคโนโลยีมือถือที่เชื่อมต่อกับโลกออนไลน์ได้อย่างรวดเร็วมากกว่าสื่อวิทยุและโทรทัศน์ที่เคยเป็นแชมป์ในเรื่องนี้ ความเร็วที่ทำได้ทันที จากทุกที่ ทุกมุมทำให้รูปแบบการรับสาร การส่งสาร และความต้องการข่าวสารของผู้บริโภคต่างไปจากเดิม Continue reading

One ambassador’s embarrassment is a tragedy, 15,000 civilian deaths is a statistic

Few things illustrate the challenges facing journalism in the age of ‘Big Data’ better than Cable Gate – and specifically, how you engage people with stories that involve large sets of data.

The Cable Gate leaks have been of a different order to the Afghanistan and Iraq war logs. Not in number (there were 90,000 documents in the Afghanistan war logs and over 390,000 in the Iraq logs; the Cable Gate documents number around 250,000) – but in subject matter.

Why is it that the 15,000 extra civilian deaths estimated to have been revealed by the Iraq war logs did not move the US authorities to shut down Wikileaks’ hosting and PayPal accounts? Why did it not dominate the news agenda in quite the same way?

Tragedy or statistic?

I once heard a journalist trying to put the number ‘£13 billion’ into context by saying: “imagine 13 million people paying £1,000 more per year” – as if imagining 13 million people was somehow easier than imagining £13bn. Comparing numbers to the size of Wales or the prime minister’s salary is hardly any better.

Generally misattributed to Stalin, the quote “The death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic” illustrates the problem particularly well: when you move beyond scales we can deal with on a human level, you struggle to engage people in the issue you are covering.

Research suggests this is a problem that not only affects journalism, but justice as well. In October Ben Goldacre wrote about a study that suggested “People who harm larger numbers of people get significantly lower punitive damages than people who harm a smaller number. Courts punish people less harshly when they harm more people.”

“Out of a maximum sentence of 10 years, people who read the three-victim story recommended an average prison term one year longer than the 30-victim readers. Another study, in which a food processing company knowingly poisoned customers to avoid bankruptcy, gave similar results.”

In the US “scoreboard reporting” on gun crime – “represented by numbing headlines like, “82 shot, 14 fatally.”” – has been criticised for similar reasons:

“”As long as we have reporting that gives the impression to everyone that poor, black folks in these communities don’t value life, it just adds to their sense of isolation,” says Stephen Franklin, the community media project director at the McCormick Foundation-funded Community Media Workshop, where he led the “We Are Not Alone” campaign to promote stories about solution-based anti-violence efforts.

“Natalie Moore, the South Side Bureau reporter for the Chicago Public Radio, asks: “What do we want people to know? Are we just trying to tell them to avoid the neighborhoods with many homicides?” Moore asks. “I’m personally struggling with it. I don’t know what the purpose is.””

Salience

This is where journalists play a particularly important role. Kevin Marsh, writing about Wikileaks on Sunday, argues that

“Whistleblowing that lacks salience does nothing to serve the public interest – if we mean capturing the public’s attention to nurture its discourse in a way that has the potential to change something material. “

He is right. But Charlie Beckett, in the comments to that post, points out that Wikileaks is not operating in isolation:

“Wikileaks is now part of a networked journalism where they are in effect, a kind of news-wire for traditional newsrooms like the New York Times, Guardian and El Pais. I think that delivers a high degree of what you call salience.”

This is because last year Wikileaks realised that they would have much more impact working in partnership with news organisations than releasing leaked documents to the world en masse. It was a massive move for Wikileaks, because it meant re-assessing a core principle of openness to all, and taking on a more editorial role. But it was an intelligent move – and undoubtedly effective. The Guardian, Der Spiegel, New York Times and now El Pais and Le Monde have all added salience to the leaks. But could they have done more?

Visualisation through personalisation and humanisation

In my series of posts on data journalism I identified visualisation as one of four interrelated stages in its production. I think that this concept needs to be broadened to include visualisation through case studies: or humanisation, to put it more succinctly.

There are dangers here, of course. Firstly, that humanising a story makes it appear to be an exception (one person’s tragedy) rather than the rule (thousands suffering) – or simply emotive rather than also informative; and secondly, that your selection of case studies does not reflect the more complex reality.

Ben Goldacre – again – explores this issue particularly well:

“Avastin extends survival from 19.9 months to 21.3 months, which is about 6 weeks. Some people might benefit more, some less. For some, Avastin might even shorten their life, and they would have been better off without it (and without its additional side effects, on top of their other chemotherapy). But overall, on average, when added to all the other treatments, Avastin extends survival from 19.9 months to 21.3 months.

“The Daily Mail, the Express, Sky News, the Press Association and the Guardian all described these figures, and then illustrated their stories about Avastin with an anecdote: the case of Barbara Moss. She was diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2006, had all the normal treatment, but also paid out of her own pocket to have Avastin on top of that. She is alive today, four years later.

“Barbara Moss is very lucky indeed, but her anecdote is in no sense whatsoever representative of what happens when you take Avastin, nor is it informative. She is useful journalistically, in the sense that people help to tell stories, but her anecdotal experience is actively misleading, because it doesn’t tell the story of what happens to people on Avastin: instead, it tells a completely different story, and arguably a more memorable one – now embedded in the minds of millions of people – that Roche’s £21,000 product Avastin makes you survive for half a decade.”

Broadcast journalism – with its regulatory requirement for impartiality, often interpreted in practical terms as ‘balance’ – is particularly vulnerable to this. Here’s one example of how the homeopathy debate is given over to one person’s experience for the sake of balance:

Journalism on an industrial scale

The Wikileaks stories are journalism on an industrial scale. The closest equivalent I can think of was the MPs’ expenses story which dominated the news agenda for 6 weeks. Cable Gate is already on Day 9 and the wealth of stories has even justified a live blog.

With this scale comes a further problem: cynicism and passivity; Cable Gate fatigue. In this context online journalism has a unique role to play which was barely possible previously: empowerment.

3 years ago I wrote about 5 Ws and a H that should come after every news story. The ‘How’ and ‘Why’ of that are possibilities that many news organisations have still barely explored. ‘Why should I care?’ is about a further dimension of visualisation: personalisation – relating information directly to me. The Guardian moves closer to this with its searchable database, but I wonder at what point processing power, tools, and user data will allow us to do this sort of thing more effectively.

‘How can I make a difference?’ is about pointing users to tools – or creating them ourselves – where they can move the story on by communicating with others, campaigning, voting, and so on. This is a role many journalists may be uncomfortable with because it raises advocacy issues, but then choosing to report on these stories, and how to report them, raises the same issues; linking to a range of online tools need not be any different. These are issues we should be exploring, ethically.

All the above in one sentence

Somehow I’ve ended up writing over a thousand words on this issue, so it’s worth summing it all up in a sentence.

Industrial scale journalism using ‘big data’ in a networked age raises new problems and new opportunities: we need to humanise and personalise big datasets in a way that does not detract from the complexity or scale of the issues being addressed; and we need to think about what happens after someone reads a story online and whether online publishers have a role in that.

The News Diamond reinterpreted: “Let the crowd have the middle”

Shuler’s amended News Diamond showing area where journalists should focus – the edges

Jonathon Shuler has published a post exploring the News Diamond from my Model for a 21st Century Newsroom. As part of that he’s added an extra layer to the diamond showing which areas professional journalists should focus on, and which ones they should let go:

“Let the crowd have the middle of the diamond. Just let it go, our time there is ending. There’s too many of them, they are too fast, they will out man and out maneuver you every time that it matters to them–and if it doesn’t matter to them, I bet there’s not much of a market for it. Just walk away… and watch.”

He finishes by arguing that commercial journalism needs to raise the bar:

“The future of Journalism is not to become public service with the hopes of gratuity, but a professional service with professional expectations and results. If people are going to blogs and the crowd instead of your publications, it’s because your publication is not meeting the expectations of your audience. As a publication you have the choice to evolve to meet those expectations, find a new audience, or leave.”

The News Diamond reimagined as ‘The Digital News Lifecycle’

Here’s a wonderful reimagining of the News Diamond from the first part of my Model for a 21st Century Newsroom. Gaurav Mishra’s diagram (shown above) takes my rhombus (shown below) and plots it against two axes. It’s rather lovely.

Helpfully, however, Mishra takes the concept forward a little. As he explains:

“my “news lifecycle” is different from Paul Bradshaw’s “news diamond” in two ways –

“1. Paul’s “news diamond” looks at news from a news organization’s perspective, whereas my “news lifecycle” acknowledges that the boundaries between news creators, news curators and news consumers have blurred beyond recognition.

“2. Paul does not make the distinction between unplanned breaking news events (like accidents and terrorist attacks) and planned live coverage of events (like the Super Bowl or the US presidential inauguration). Paul’s “news diamond” and my “news lifecycle” models are much more valid for unplanned breaking news events.”

It’s fair to say that my diamond does take the perspective of a news organisation – that’s who it was aimed at. But I’m not sure that that means it doesn’t acknowledge the blurring of boundaries.

Anyway, Mishra poses some questions:

- How do we increase the number and variety of sources in the process of creating, curating and consuming news?

- How do we separate signal from noise during each stage of the news lifecycle?

- How do we contract the “alert” to “analysis” stages of the news lifecycle, in order to get better signal to noise ratio sooner in the cycle?

- How to we expand the “conversation” to “customization” stages of the news lifecycle, in order to maximize the returns from the content we have created?

- How do we expand the requisite participatory media ecosystem so that exceptions to this news lifecycle (like the information void in the Israel-Hamas Gaza conflict or the Russia-Georgia Otessia conflict) become increasingly rare?

I’d be very interested in any responses.

In the meantime, here’s those original diagrams for your conceptual enjoyment…

As it happens, the diamond was just another way of showing the following flow diagram from the same post, so now I have 3 diagrams to refer to…

More 21st century newsroom ideas: the Google Newsroom

Here’s a new contribution to the ‘Model for a 21st Century Newsroom’ concept: the Google Newsroom, by Benoît Raphaël. Based on his experience as editor in chief at Le Post, Raphael makes a number of salient points about reorganising the newsroom in a digital age. He suggests that “we have to forget that old idea of merging newsrooms” and create “one “where everything happens,” that is to say on the web. This is the heart of information system. The rest is just appearance.” Continue reading

What I expect at news:rewired — and what I hope will happen

Next Thursday is the news:rewired event at City University London, which is being put on by the good people at journalism.co.uk. I’ll be on hand as a delegate.

Next Thursday is the news:rewired event at City University London, which is being put on by the good people at journalism.co.uk. I’ll be on hand as a delegate.

All of the bases will be covered, it seems: Multimedia, social media, hyperlocal, crowdsourcing, datamashups, and news business models.

Model for a 21st Century Newsroom – in Spanish

In April Maxim Salomatin translated the Model for a 21st Century Newsroom series into Russian. Now Mauro Accurso has translated it into Spanish. All 6 parts, which make up around 10,000 or so words. It’s an incredible feat, and I’m enormously grateful.

So, here they are, part by part:

- Part 1: The News Diamond – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/09/02/el-diamante-de-noticias-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xx1-1ra-parte/

- Part 2: Distributed Journalism – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/09/07/periodismo-distribuido-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xxi-2da-parte/

- Part 3: 5 Ws and a H that should come after every story – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/09/21/6-preguntas-que-deberian-venir-despues-de-cada-noticia-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xxi-3ra-parte/

- Part 4: News distribution in a new media age – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/10/06/la-distribucion-de-las-noticias-en-un-mundo-de-nuevos-medios-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xxi-%e2%80%93-4ta-parte/

- Part 5: Making money from journalism online: new media business models – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/11/02/ganando-plata-con-el-periodismo-modelos-de-negocio-de-los-nuevos-medios-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xxi-5ta-parte/

- Part 6: New journalists for new information – http://tejiendo-redes.com/2009/11/11/nuevos-periodistas-para-un-nuevo-flujo-de-informacion-modelo-para-la-redaccion-del-siglo-xxi-%e2%80%93-6ta-parte/

(As an aside, The Spanish Press Association approached me last year for permission to translate it too but I’ve never seen it. Perhaps they got bored after part 1… or perhaps they’re just rude. Anyway, if you’ve seen it, let me know.)

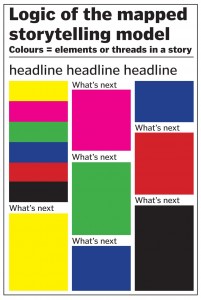

“Mapped” writing model takes a layered approach to news

If the inverted pyramid as a writing form is tied to the printed page, what writing form does the web suggest?

That was the question asked by João Canavilhas of Portugal when he proposed the “tumbled pyramid,” a more open story architecture designed to encourage online navigation and personal reading paths. Canavilhas describes a new structure with four levels: base, explanation, and two levels of exploration.

I’ve wrestled with the same question. My solution: the “mapped” writing model (interesting how we reach out to new metaphors to replace old ones). Where my approach differs is its simplicity. The mapped model is really just a specific way to organize information. It assumes little change in how you, as the practitioner, define a story or function as a journalist. I’d like to explain the concept and how it rethinks the inverted pyramid.

HOW IT WORKS:

The mapped model views the news story as a whole and parts. First comes a summary of the main elements. Then the story breaks into an orderly conversation of one element or thread at a time. It’s up to the writer to define the content threads. Each thread starts with a subhead that clearly conveys what comes next, for example: “what happened,” “what witnesses saw,” or “next steps in the process.” The subheads function as a map, telling readers ahead of time where the story will lead, what turns in the road they can expect, and reminding them where they are. This form seems to work best on longer news and feature stories.

Below is a simple example of a mapped story I wrote recently for our community newspaper. I presented the story experimentally in a simple Flash file, to see how it might look on the web. You won’t be wowed by zippy graphics. It’s meant to show how the subheads can become the means of navigation, literally. On the web you could also present this story as a continuous text, with subheads set into the story, acting as signposts.

ORIGIN OF THE CONCEPT:

I developed this model as a news designer a few years ago as I tried to imagine ways to make stories easier to read.

I was troubled by what seemed like information chaos in many news stories dealing with complex topics. With a background in writing, I began to analyze how stories were built. I used color markers to highlight the various categories or threads present in a story, wherever they showed up in the text (I choose the colors at random). For example, “background” might turn up as a block of yellow in the second paragraph, then again in the sixth paragraph, then as a chunk toward the end of the story. Fully deconstructed, the story might contain six or eight threads, showing up as a patchwork of colors. Continue reading