In a guest post Jane Haynes speaks to investigative journalist Peter Geoghegan of the award-winning news site The Ferret about data, contacts and “nosing up the trousers of power”.

When the Scottish Government announced last month that it was banning fracking, it was a moment to savour for a group of journalists from an independent news site in the heart of the country.

The team from investigative cooperative The Ferret had been the first news organisation to reveal plans by nine energy companies to bid for licences to extract shale gas from central Scotland.

Using a combination of contact-led information and FOI requests, they uncovered the extent of the ambitions to dig deep into Scottish soil.

It was part of a steady flow of fracking stories from the Ferret team, ensuring those involved in making decisions were in no doubt of their responsibilities and recognised that every step would be scrutinised.

Holding power to account

The Ferret’s mission statement includes this pledge:

“With everyone’s help and experience, and independent financial backing, we can cover important issues the mainstream media often misses.

“Whatever happens, The Ferret will be nosing up the trousers of power.”

It’s a bold statement, but a quick glance through the issues being covered by the team right now shows they are doing their damnedest to hold power to account.

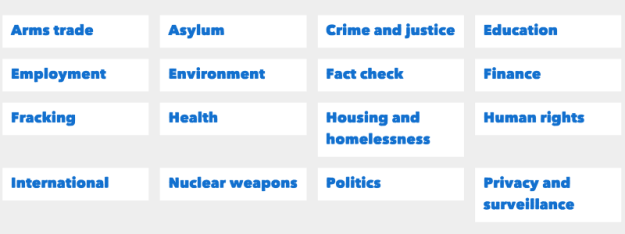

Recent Ferret inquiries have uncovered how the Leave campaign was funded during the EU Referendum, focussing particularly on fundraiser Arron Banks, and raised issues around the arms trade, human rights, homelessness and environmental issues.

Peter Geoghegan not only fronts up the Ferret; his journalism also embodies the traits associated with the tenacious beast its named after.

He’s carved out a reputation as a persistent and dogged journalist who doesn’t give up on a quest easily.

When others fall by the wayside, bogged down by repeatedly rejected FOI requests, complex datasets or stonewalling officials, Peter just keeps digging, seeking out that ‘something’ that will bring a story to life.

His recent investigations have focused on Arron Banks and his influence in the Leave campaign during the EU Referendum; DUP funding; and the impact of the Catalan battle for independence.

He’s also told the story of Scotland’s historic Referendum vote, from the perspective of the ordinary people involved, in his book The People’s Referendum: Why Scotland Will Never Be the Same Again, published in January 2015 by Luath Press.

His work regularly appears in traditional media, including The Guardian, and on the website Politico.

Peter will be part of a panel of experts at next month’s second annual Data Journalism UK conference in Birmingham discussing how to use data effectively to find and tell stories.

The event, at BBC Birmingham in The Mailbox on December 5, is an opportunity for journalists, scholars and students to share examples of cutting edge reporting, learn about techniques for finding stories in structured information and see how great data journalism works.

Fracking and FOI

Peter recalls the Ferret’s first foray into investigation:

“Fracking was our first topic for investigation — we were a group of people concerned that things were happening that weren’t being openly discussed.

“Using FOI requests, we got hold of details about which parcels of land were being earmarked as test sites, enabling us to slowly build up a picture of the extent of the plans.

“We were able to piece together the information and use the data to summarise the situation and make people aware of the story.”

It wasn’t the first time that using the Freedom of Information Act had been the difference between having a sense of a story and being able to flesh it out.

It’s a device that seems to help journalists and residents lay bare the machinations of national and local decision-making and spending.

Indeed, it should be that a combination of the FOI Act and the rise of open data ensures we are free from the tyranny of secretive power dealing and protectionism.

But we are still a long way from that, says Peter:

“We’re still not seeing anything close to open transparency from some organisations, which continues to be a challenge for journalists.

“We are seeing officials and people in power becoming increasingly aware of how to get around FOIs — not putting information into emails, for example, and having informal verbal discussions instead.

“We’re also facing press officers who routinely turn down simple requests for information and instead tell journalists to submit an FOI, which of course can delay us getting to the information we need to support a story.”

He adds: “For new journalists, my main message would be not to rely on digital tools to find stories.

“People and contacts are still the most important elements. Old-school curiosity, investigation through talking to people, winning people’s confidence and asking the right questions remain the most important skills for a journalist.

“My starting point for a story is always something that I have heard or found out through talking to people. Data alone is not a replacement for that.

But computer literacy and investing in data understanding “is increasingly important,” he says.

“Every journalist should know the basics of how to manipulate a spreadsheet, create a pivot table, and understand what the data represents.

“Data is not just numbers either — data can describe email exchanges and communications in words or images too.

“Understanding of how to interrogate data is also the only way to really get to the heart of big data. There has been a technological shift which means journalists are now able to deal with large data sets like the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.”

Hyperlocal and alternative journalism — “no quick solution”

Peter is also a passionate advocate for independent, alternative journalism — what’s sometimes referred to as the hyperlocal sector but which has come to embrace national collaborative organisations like The Ferret.

How these new media players turn a voluntary ‘passion project’ into a sustainable, coherent financial model is the as yet unanswered question. Says Peter:

“There is no quick solution. These are often very slow-build projects; it takes time and effort to get to the stage of being able to pay contributors, for example.”

The Ferret is a cooperative, with funding coming from subscribing members who also have voting rights over the stories the organisation covers.

In addition the Ferret is supported financially by a grant from Google News Lab.

“A community-led model like ours seems to be the approach that is most likely to be sustainable in the long term.”

Appearing alongside Peter at #DJUK17 will be keynote speaker Megan Lucero from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s Bureau Local project, which was established with £500,000 from Google’s Digital News Innovation Fund to support data journalism at a local and regional level.

Other speakers include Peter Sherlock from the BBC’s shared data unit; Karrie Kehoe from RTE’s investigations unit; Emma Youle from Archant’s investigation team; and Aasma Day from Lancashire Post’s investigations team. More information and tickets are available here.

Jane Haynes is a student on the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism at Birmingham City University.

Reblogged this on do not drop the ball and commented:

Date does not count untold stories…

Pingback: L'avenir du journalisme - revue de presse du 15 décembre - Cladelcroix