By starting from one person you can start to identify the different parts of the systems that affect your topic — and useful story leads and ideas

For the last couple of weeks I’ve been helping students on my MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism and MA in Data Journalism come up with story ideas for specialist reporting and investigations. Part of the process involves an exercise around scoping out a particular subject or system you are interested in — for example, the housing system, or ‘dark kitchens’, the Oscars, or air pollution — and identifying the gaps in your knowledge that can lead to stories.

It’s an exercise where empathy plays a central role.

Here’s how the process works — and why empathy is so important to it.

Start with a person at the heart of your subject

Specialist reporters and investigative journalists may report on subjects, but ultimately the stories that matter around those subjects affect people.

For example, health issues affect patients and their families; transport issues affect passengers using trains, or cars, or buses. Environmental issues might affect a resident in an area affected by flooding, or a worker in a sweatshop — or you could even put an animal at the heart of your subject.

Taking a subject and identifying a person at the heart of that subject is a good way to begin to understand those human impacts of a system.

Let’s start with a subject that people often want to report on: homelessness.

Who is a person especially affected by homelessness? The obvious answer is a homeless person. So start there.

This doesn’t mean your story will be about that person — it just gives you a starting point in finding all sorts of other people and ideas in covering that subject.

In the middle of a big sheet of paper draw a circle. Write ‘homeless person’ in the circle.

This is the starting point in mapping the systems in the subject we want to report on.

Add the people they come into contact with

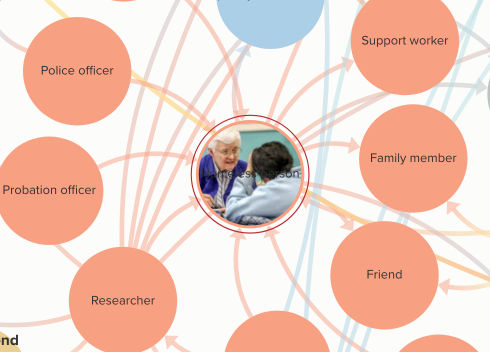

A diagram might start something like this, with the person at the centre and other people connected to them

Now to begin to empathise: think about the people that this person regularly encounters: the people who shape his/her life and whose lives he/she shapes.

There are some which will apply to almost anyone:

- Friends

- Family

There are some which may be specific to your chosen person:

- Strangers

- Support service worker

- Police officer

Of course not every homeless person will come into contact with all of the people above. Just because someone is homeless doesn’t mean they are living on the streets; they may not access support services; they may not come into contact with strangers, or police.

Who seeks that person out?

You can also think about people who come into contact with your person because they seek that person out. For example:

- Researchers

- Journalists (of which you are one)

Note that each element is a person — try to avoid organisations for now (we will come to them later). As people we normally have interactions with other people, even if they represent an organisation.

For example a person might be paid to do some work, but their contact with that organisation is through their boss. They might have colleagues. They might have customers. They might rent a flat, but their connection with that flat is through a landlord.

Why do we put these down instead of their organisations? Partly because it helps us to empathise once again. Why does the boss act the way they do? The police officer? The landlord?

But it’s also because these might lead us to interviewees. Can we speak to a boss? A police officer?

Adding imagination: what are the problems?

Now try to imagine a specific person in that situation. How did they arrive here? Where are they trying to get to?

Explore what problems are involved with that person’s situation. Imagination is more effective when it’s fed with information. So read widely about the subject.

The more you read around the subject, the more connections you can add. For example, you might read about people becoming homeless after being released from prison. You might hear about solicitors being involved as they try to get housing, so you add them to the list. You might read about the role of domestic abuse in homelessness. Now we have:

- Probation officer

- Solicitor

- Housing adviser

- 999 call centre (when reporting domestic abuse)

- Refuge worker

Keep adding to this with other potential connections the more that you read.

Filling the gaps

There will be gaps in your map — in fact, this is part of its purpose.

The point is not to tell you what you already know, but to highlight the areas where stories perhaps haven’t been done, and/or where you can focus your efforts.

Add circles for things that you don’t know. For example you might read about the high prevalence of problematic drug/alcohol use but not know yet who deals with that. You put something like:

- Drug dealer

- Addiction services worker??

And highlight the second as a thread to pick up.

Later you can do some research to find out who their first port of call is for treatment of that — you can now fill in those gaps:

- GP

- Pharmacist

- Therapist

Already you might be able to spot (and note) potential story ideas: in this case, how does a person without an address get a GP? Do they have to pay for prescriptions and if not, does that leave a data trail?

Reading, watching and talking to expand further

Expand your reading so that you are covering all three of the following:

- Not just about the people you are empathising with but…

- By the people you are empathising with and

- For the people you are empathising with

Speak, watch and listen too:

- Speak/listen:

- To the people you are empathising with,

- Those who work with them,

- Those who work for them,

- Those who they work for

- Watch the people you are empathising with — for example by attending events

By this point you should have a much richer understanding of the person at the heart of your story, who they come into contact with, what their history might be — in fact, it should no longer be a person, but a number of people, with different routines, histories and problems. Already a number of story ideas should be starting to open out that perhaps weren’t there before.

Now we can expand the diagram beyond that first circle.

Who calls the shots? Bringing in organisations

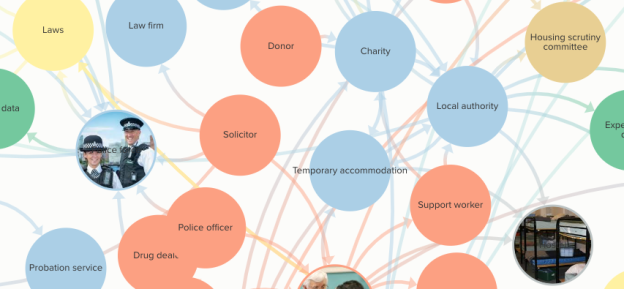

We now add organisations, which lead to other people

You now have a circle of people around your focal person. Each of those people does not act with complete freedom. Their actions are constrained and guided by institutions. For example:

- A probation officer is employed by the probation service, has a contract of employment, must follow certain procedures and obey certain rules

- A solicitor is employed by a law firm, with different rules and procedures, and working culture

- A support worker might work for the local authority, or work for a charity — a charity which has in turn been contracted by the local authority to deliver its services

- A drug dealer might be part of an informal organisation with its own ‘codes of conduct’

Note that friends and family do not need to be attached to institutions, because these will vary too much.

These institutions can lead you in turn to more people — the ones calling the shots.

You might already know who is responsible in those organisations, but chances are that this might be another gap in your knowledge to highlight and fill.

Researching organisations

You can now begin to look for documents published by those organisations about the issue you are exploring.

Pay particular attention to who is the author of those documents, and which people within the organisation are named. These are the people who deal with that issue and may be best to speak to. Add them to your diagram.

Look also at why the documents were created: were they presented to some sort of scrutinising body, for example? That might be internal (local authorities have scrutiny committees tasked with checking what is being done with public money), or it might be external (regulators, other parts of government)

In my homelessness map, for example, this sees me add a councillor for housing, and a housing scrutiny committee.

And at this point we might start to uncover specific names: a specific councillor for housing, for example, that we can add. This is another potential interviewee.

Adding rules and other documents

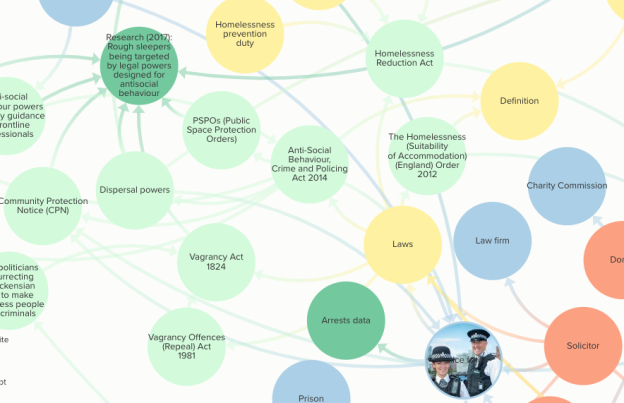

We now add law to our map – and other documents such as guidelines and duties that the organisations must follow

Documents are a third type of element in addition to the people and organisations, and it’s useful to add those to our map so that we can find them again later.

Documents are also a way of storing the rules that organisations are expected to abide by. These include:

- Laws

- Regulations that they have signed up to

- Agreements to be inspected at particular times

- Contracts they have signed

- Targets they have been given, or agreed

- Documents that they must publish

- Data that they must share

With the homelessness map, for example, we identified ‘police officer’ and connected them to a police force, but what rules are the police forces following?

This is a gap that we can highlight — and fill. (It turns out there are many laws that the police rely on when dealing with homelessness).

Likewise we identified a support worker and the local authority employing them — but why are they providing those services? We can find policies that they are following, duties that they are bound by, and laws which require them to act.

Again, the more reading, watching and listening that you do around the subject, the more you will spot these — and make a note of it. Eventually you start to think of connections like this.

Adding the power behind the rules

Of course the rules do not enforce themselves — so another thing we can do is use them to lead us to other institutions responsible for enforcing them. They might include:

- Law enforcement

- Those monitoring law enforcement

- Regulators (there may be more than one)

- Funders (who draw up a contract, and may set targets and/or rules)

As at every stage, this will highlight gaps in your knowledge which might also lead to potential interviews or backgrounders.

Adding concepts

At various points you will encounter words or phrases that need pinning down and defining: concepts. Those might even be quite central to your subject. For example, “homelessness” itself is a concept, as is “addiction”, “sofa surfing” and “domestic abuse”.

Concepts are tricky because they are used in different ways by different people. One person’s concept of ‘homelessness’ might mean ‘living on the streets’ while another’s might be ‘does not have a permanent address’.

As professional communicators we need to have a firm grasp on the words that we are using and what they actually mean.

And as professional listeners — interviewers — we need to be ready to ask someone to clarify a concept when they refer to it.

Concepts also have power. Documents and rules might define, or refer to definitions, to clarify when and how action must be taken.

What should happen and what does happen

Those rules and documents, the concepts they define, and the organisations responsible for enforcing them, are where this process really starts to pay out, in terms of story ideas. We can now ask:

- Are those with power doing what they said they would do? (In the documents, policies, etc)

- Are rules being ignored?

- Are rules being misused or abused or used in a way that was never intended?

- Are rules being enforced?

- Are the rules or policies effective in what they are supposed to achieve? Are there loopholes?

- Are the rules leading to unforeseen behaviour and results? (E.g. target chasing)

- Is monitoring uncovering problems that people don’t know about? (Hidden in documents, e.g. data)

All of these are classic starting points for an investigation.

Simpler, quicker story ideas that help you get to the bigger ones

But we can also identify much simpler story ideas which might be stepping stones to bigger ones. For example:

- Are there people in this network that we could do a profile feature on? An interview feature?

- Are there organisations that we could do a feature on? (For example campaign groups or charities trying to facilitate change, or companies trying to solve a problem)

- Are there events that take place which we could write a news report on or feature about?

- Are there systems or little-known practices that we could do an explainer on? (If we want to know how it works, or were surprised that a particular practice or policy existed, perhaps a particular audience would too)

- Are there histories that we could do a backgrounder on? (How did this law come to pass? Why was this organisation created)

- Is there data here that we could do data journalism with? (Looking at whether things are getting better or worse, or which areas are top/bottom, or an infographic explainer)

- Are there documents or data that we could request via FOI for a story? (Correspondence behind a decision, or a contract which was agreed, or complaints made)

It is often these smaller stories which lead us to the bigger ones — partly because they enhance your understanding of the field, but perhaps more because they build relationships and contacts, and create a profile and reputation for covering this subject which may lead people to seek you out with more stories.

Keeping track — using network mapping tools

This exercise is just a starting point. As your research/reporting/investigation proceeds, you will see more parts of the system, and need to add it to your system map.

But if you’re doing this on a piece of paper, it very quickly gets crowded and difficult to organise. Instead, it’s more useful to do this online with a network mapping/analysis tool like Kumu that will allow you to filter, search and download the information you are collecting — as well as access it from anywhere.

Here are some examples to demonstrate how it can be used:

- Mapping the systems around student accommodation

- ‘Dark kitchens‘

- Cyber security

- Homelessness (system version)

- Homelessness (stakeholder version)

A network mapping the system around homelessness, used to generate story ideas and keep track of research.

This is especially useful if you are collaborating on a project: you can add contributors who can add their own information to the network map as they go.

You can choose from a Stakeholder map (which has the advantage of reorganising itself as you add new information), or a System map (which stays fixed). In both cases you add people, organisations and documents as ‘elements‘ (nodes) in a network, and add connections between those.

Hovering over any element will then highlight only the elements which it is connected to.

You can categorise elements and connections. ‘Person’ or ‘organisation’ are defaults but you can also add your own to the list, such as ‘document’, ‘data’ and ‘concept’.

You can then style the diagram to use different colours for different categories.

You can add notes and images to any element in the description area — useful for adding links to documents or data, or profiles of individuals and company information pages.

And as you build the network the data is stored in tables which can be downloaded, sorted and filtered too (alternatively, you can also upload data from spreadsheets in order to create these network maps).

A tool like Kumu can also be used to communicate part of a network to others. However, note that this is using the tool for a different (non-exploratory/documentation) purpose, and so is likely to be a smaller subset of the system that you’ve been exploring, containing only those elements which you want to tell a story about. More information on this approach can be found in the video below.

Pingback: Pandeminin Toplumsal Etkilerini Verilerle Anlatmak – Sedat Erol

Pingback: A journalist’s introduction to network analysis | Online Journalism Blog

Pingback: A journalist’s introduction to network analysis – Totally news