Something interesting happened to journalism when it moved from print and broadcast to the web. Aspects of the process that we barely thought about started to be questioned: the ‘story’ itself seemed less than fundamental. Decisions that you didn’t need to make as a journalist – such as what medium you would use – were becoming part of the job.

In fact, a whole raft of new decisions now needed to be made.

For those launching a new online journalism project, these questions are now increasingly tackled with a content strategy, a phrase and approach which, it seems to me, began outside of the news industry (where the content strategy had been settled on so long ago that it became largely implicit) and has steadily been rediscovered by journalists and publishers.

‘Web first’, for example, is a content strategy; the Seattle Times’s decision to focus on creation, curation and community is a content strategy. Reed Business Information’s reshaping of its editorial structures is, in part, a content strategy:

Why does a journalist need a content strategy?

I’ve written previously about the style challenge facing journalists in a multi platform environment: where before a journalist had few decisions to make about how to treat a story (the medium was given, the formats limited, the story supreme), now it can be easy to let old habits restrict the power, quality and impact of reporting.

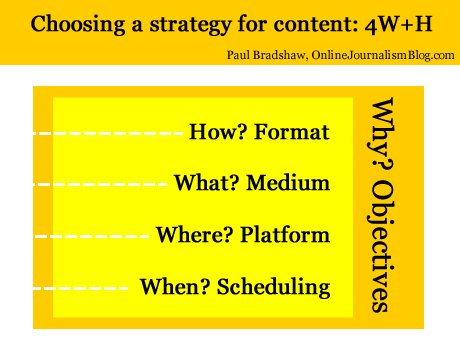

Below, I’ve tried to boil down these new decisions into 4 different types – and one overarching factor influencing them all. These are decisions that often have to be made quickly in the face of changing circumstances – I hope that fleshing them out in this way will help in making those decisions quicker and more effectively.

1. Format (“How?”)

We’re familiar with formats: the news in brief; the interview; the profile; the in-depth feature; and so on. They have their conventions and ingredients. If you’re writing a report you know that you will need a reaction quote, some context, and something to wrap it up (a quote; what happens next; etc.). If you’re doing an interview you’ll need to gather some colour about where it takes place, and how the interviewee reacts at various points.

Formats are often at their most powerful when they are subverted: a journalist who knows the format inside out can play with it, upsetting the reader’s expectations for the most impact. This is the tension between repetition and contrast that underlies not just journalism but good design, and even music.

As online journalism develops dozens of new formats have become available. Here are just a few:

- the liveblog;

- the audio slideshow;

- the interactive map;

- the app;

- the podcast;

- the explainer;

- the portal;

- the aggregator;

- the gallery

Formats are chosen because they suit the thing being covered, its position in the publisher’s news environment, and the resources of the publisher.

Historically, for example, when a story first broke for most publishers a simple report was the only realistic option. But after that, they might commission a profile, interview, or deeper feature or package – if the interest and the resources warranted that.

The subject matter would also be a factor. A broadcaster might be more inclined to commission a package on a story if colourful characters or locations were involved and were accessible. They might also send a presenter down for a two-way.

These factors still come into play now we have access to a much wider range of formats – but a wider understanding of those formats is also needed.

- Does the event take place over a geographical area, and users will want to see the movement or focus on a particular location? Then a map might be most appropriate.

- Are things changing so fast that a traditional ‘story’ format is going to be inadequate? Then a liveblog may work better.

- Is there a wealth of material out there being produced by witnesses? A gallery, portal or aggregator might all be good choices.

- Have you secured an interview with a key character, and a set of locations or items that tell their own story? Is it an ongoing or recurring story? An audio slideshow or video interview may be the most powerful choice of format.

- Are you on the scene and raw video of the event is going to have the most impact? Grab your phone and film – or stream.

2. Medium (“What?”)

Depending on what format has been chosen, the medium may be chosen for you too. But a podcast can be audio or video; a liveblog can involve text and multimedia; an app can be accessed on a phone, a webpage, a desktop widget, or Facebook.

This is not just about how you convey information about what’s going on (you’ll notice I avoid the use of ‘story’, as this is just one possible choice of format) but how the user accesses it and uses it.

A podcast may be accessed on the move; a Facebook app on mobile, in a social context; and so on. These are factors to consider as you produce your content.

3. Platform (“Where?”)

Likewise, the platforms where the content is to be distributed need careful consideration.

A liveblog’s reporting might be done through Twitter and aggregated on your own website. A map may be compiled in a Google spreadsheet but published through Google Maps and embedded on your blog.

An audioboo may have subscribers on iTunes or on the Audioboo app itself, and its autoposting feature may attract large numbers of listeners through Twitter.

Some call the choice of platform a choice of ‘channel’ but that does not do justice to the interactive and social nature of many of these platforms. Facebook or Twitter are not just channels for publishing live updates from a blog, but a place where people engage with you and with each other, exchanging information which can become part of your reporting (whether you want it to or not).

(Look at these tutorials for copy editors on Twitter to get some idea of how that platform alone requires its own distinct practices)

Your content strategy will need to take account of what happens on those platforms: which tweets are most retweeted or argued with; reacting to information posted in your blog or liveblog comments; and so on.

[UPDATE, March 25: This video from NowThisNews’s Ed O’Keefe explains how this aspect plays out in his organisation]

4. Scheduling (“When?”)

The choice of platform(s) will also influence your choice of timing. There will be different optimal times for publishing to Facebook, Twitter, email mailing lists, blogs, and websites.

There will also be optimal times for different formats (as the Washington Post found). A short news report may suit morning commuters; an audio slideshow or video may be best scheduled for the evening. Something humorous may play best on a Friday afternoon; something practical on a Wednesday afternoon once the user has moved past the early week slog.

This webcast on content strategy gives a particular insight into how they treat scheduling – not just across the day but across the week.

5. “Why?”

Print and broadcast rest on objectives so implicit that we barely think about them. The web, however, may have different objectives. Instead of attracting the widest numbers of readers, for example, we may want to engage users as much as possible.

That makes a big difference in any content strategy:

- The rapid rise of liveblogs and explainers as a format can be partly explained by their stickiness when compared to traditional news articles.

- Demand for video content has exceeded supply for some publishers because it is possible to embed advertising with content in a way which isn’t possible with text.

- Infographics have exploded as they lend themselves so well to viral distribution.

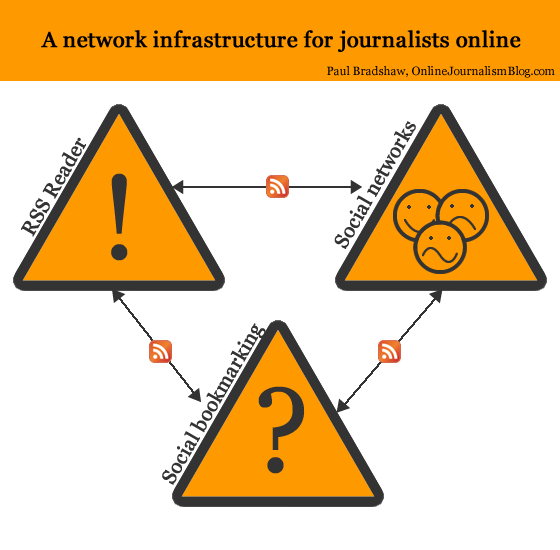

Distribution is often one answer to ‘why?’, and introduces two elements I haven’t mentioned so far: search engine optimisation and social media optimisation. Blogs as a platform and text as a medium are generally better optimised for search engines, for example. But video and images are better optimised for social network platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

And the timing of publishing might be informed by analytics of what people are searching for, updating Facebook about, or tweeting about right now.

The objective(s), of course, should recur as a consideration throughout all the stages above. And some stages will have different objectives: for distribution, for editorial quality, and for engagement.

Just to confuse things further, the objectives themselves are likely to change as the business models around online and multiplatform publishing evolve.

If I’m going to sum up all of the above in one line, then, it’s this: “Take nothing for granted.”

I’m looking for examples of content strategies for future editions of the book – please let me know if you’d like yours to be featured.