In a previous post I outlined seven habits often associated with good journalism that are often talked about (wrongly) as ‘innate’ or ‘unteachable’. In this second post I look at scepticism: why it’s so important in journalism, and how it can be taught.

On its own the first habit of a successful journalist — curiosity — can only take us so far as a journalist: as we ask questions of our sources, we cannot merely report what people tell us — especially if two different sources say contrasting things.

Scepticism is important in journalism because it moves us from merely repeating what people have said, to establishing the factual basis that puts that information into context — whether those facts support or contradict those statements, or do not exist at all.

This has become particularly important in a modern information age when most public bodies can communicate with the public directly, without that accountability.

Scepticism as the voice of the audience

If curiosity represents the journalist acting as the eyes and ears of the audience, scepticism is where we act as the mouth of the audience.

More specifically, it is the way in which we give a voice to an audience which isn’t able to ask questions itself.

This conception of scepticism provides a useful method for teaching scepticism: while compiling statements and other evidence in a story, you can ask the trainee journalist:

- “If your reader was in the room/on the call/sending the email, what would they ask this person?”

- “What questions might your audience ask about the evidence you’ve been given?”

- “What extra information might they need to make sense of it?”

Conceiving of the audience in different ways helps too. An ‘average reader’ might ask different questions to one who works in the field being reported on. They in turn might have different doubts to the academic expert who studies it.

An exercise that raises those questions for each is another way of developing sceptical habits.

This can also help in phrasing questions to a source, helping the interviewee to understand that you are not casting doubt on what they’ve said, but only making sure that your audience understands it, or acting to provide a platform for public debate. Examples include:

- “Your political opponents might suggest that your motivations are financial. What is your response to that?”

- “Our readers might ask how you can know that if you weren’t there?”

- “Those studying the data on this overwhelmingly say that the opposite is true. What evidence is your claim based on?”

- “Your employees might be sceptical of that claim. How would you respond to that?”

Of course the reporter doesn’t have to take on those roles: they can seek out those opposing viewpoints, and contextual evidence, themselves, and refer to it in their questioning.

This highlights that scepticism isn’t merely a personal trait of the journalist, but a procedural habit, too. A good journalist researches the issues they report on, and speaks to a wide range of people to get a range of perspectives.

Of course they must have the skills to do so — and treat each source with the same scepticism, too.

Scepticism frameworks: verification and data biographies

Other procedures for incorporating scepticism are found in the fields of modern verification practice and data journalism.

Heather Krause, for example, outlines the process of compiling a ‘data biography‘ when working with a dataset, asking questions about where it came from, who collected it, how it was compiled and why. A template can be used that includes two examples.

More broadly Darrell Huff’s seminal How To Lie With Statistics is a great quick read on how sources can frame data to mislead. And Tim Harford’s How To Make The World Add Up provides a worthy counterpart for the coronavirus age, highlighting how sources often attempt to cast doubt on data, and the importance of acknowledging uncertainty.

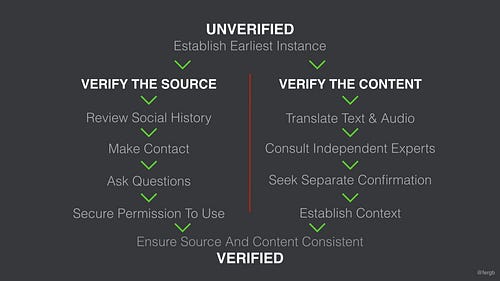

In the field of verification there are a range of models for ensuring you are asking the right questions of information, from my own ‘Content, context and code’ framework to NPR’s fact-checking triage, the source/content verification flowchart of First Draft’s Fergus Bell and Claire Wardle’s checklists for videos and images.

Scepticism and imagination — and cynicism as a failure of imagination

Scepticism is also another example of the journalist exercising their imagination: the sceptical journalist must always ask “But what if this information is not true?” — what if?

Asking “What if?” is a simple exercise to get trainee journalists to challenge the version of events they are being presented with.

- ‘What if they are lying?’;

- ‘What if they didn’t witness it directly?’;

- ‘What if they misunderstood?’;

- ‘What if they misheard?’;

- ‘What if they have a reason to omit key information?’

The role of imagination helps us distinguish scepticism from cynicism. The cynic assumes that they are being lied to; cynicism is a failure of imagination — a failure to imagine that you are not being lied to. It is just as lazy as being credulous (a credulous person fails to imagine that they are not being told the truth).

In his book We Are Bellingcat, the open source investigator Eliot Higgins identifies how this lack of imagination actively works in opposition to journalism as a defining trait of the “Counterfactual Community”: trolls and conspiracy theorists who propagate hoaxes and undermine original reporting by calling it ‘fake news’:

“A rhetorical reflex of the Counterfactual Community is endless queries, never pausing to absorb the replies. If I direct them to our exhaustive research, they pivot to the next question. This shell game implies that evidence should be disregarded because political manipulation lurks everywhere … What strikes me most is their lack of dissonance: they failed to prove the previous claim, or the one before, yet make the next with equal certainty.”

The sceptic, in contrast, is comfortable with (but not accepting of) the uncertainty of not knowing whether something is true or false.

It is a difficult position for the journalist to occupy, because uncertainty is not welcomed in the newsroom or in the news report: we deal with facts.

How, then, does the newsroom handle uncertainty? Mainly with attribution: “police said”; “the MP for Rochdale said”; “a witness said”.

With no time to establish the veracity of these accounts, and a deadline looming, we can only report what was said, not what happened.

This is an important distinction to make, and one that trainee journalists learn early on: do not report what someone has said as fact, if you cannot establish it yourself.

The failure to do this has led to some of journalism’s most shameful moments, where journalists have acted as the voice of power, rather than its sceptical watchdog.

Familiarising trainee journalists with these shameful moments — and also the proud ones — should be a central part of journalism education.

In the UK the Sun‘s Hillsborough front page that led to a decades-long boycott of the newspaper in Liverpool is one. The “six days of substantially false coverage” of the death of newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson is another, and tweets by prominent political correspondents about an assault on a political adviser during the 2019 general election are a good example of the dangers of a lack of attribution.

In the US Will Bunch relates a list of examples from just one month in his article When media rely on what police say, they miss key truths about crime, black communities:

“The initial Minneapolis police statement on Floyd’s May 26 death claiming that cops “noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress” with no mention that officers were kneeling on him and, according to prosecutors, suffocating him; the report on Louisville police-shooting victim Breonna Taylor listing her injuries as “none” when she’d been fatally riddled with eight bullets; or a Buffalo police statement that brain-injured 75-year-old protester Martin Gugino “tripped and fell” even though a news camera showed cops violently shoving him down.”

Understanding the cognitive biases that lead to these mistakes is just as important. My posts A journalist’s guide to cognitive bias (and how to avoid it), and How to prevent confirmation bias affecting your journalism provide an introduction.

For a constructive counterpart to the examples of scepticism failure, BuzzFeed’s 2017 investigation Blue Lies Matter provides an example of the methods that can be used to check official versions of events:

“BuzzFeed News reviewed 62 incidents of video footage contradicting an officer’s statement in a police report or testimony. From traffic stops to fatal force, these cases reveal how cops are incentivized to lie — and why they get away with it.”

Methods for developing scepticism

Listing the facts in a story, and then attributing each of those, is a useful exercise for developing this skill (and also one which is helpful to the legal team when a story may be defamatory). This turns each fact into a claim.

The journalist then has to explicitly decide whether to:

- Report it as a widely accepted or acknowledged fact whose source has no relevance to the story;

- Attribute the statement to allow the audience to make a decision as to its trustworthiness, including any relevant information that may inform that decision (for example, the person has a vested interest);

- Perform some additional checks to establish what basis there is for the claim (this includes a ‘what if’ exercise to explore reasons for the claim not being accurate);

- Omit the claim from the report

Establishing facts is not an exact science: in the example in the previous post a report might say that ‘Police have arrested a man following a crash on Chester Road’ even though they have not observed the crash themselves, or seen the man in question or his arrest. They might do so because they have no reason to believe the police would mislead them over such an innocuous event.

However, when dealing with other parts of the story, particularly those which may be subject to some debate in future, they might be more cautious: ‘Police say the vehicle was travelling at over 50mph when it collided with another vehicle’. How do they know the vehicle was travelling that fast, or that it collided?

Scepticism allows us to make these decisions, but on its own it is not enough for great journalism: we must be able to pursue the facts that will allow us to better establish what the facts actually are; to move from ‘not knowing’ to ‘knowing’. And that requires persistence.

In the next post, then, I tackle the third habit of successful journalists: the thing that comes after failure…

Audiences have a huge problem with the line between cynicism and scepticism. Often being sceptical about someone a reader agrees with is seen as cynicism. This is especially true in political reporting where there are two camps with little common ground. It’s made worse because a lot of what looks like journalism is politically partisan. I’m not sure how we, as a profession, can overcome this.

There is something worse to overcome, when politically partisan members of the audience blindly agree.

I am both, sceptic and cynic about journalists in general, who without realizing, are solid supporters of the status quo.

As a clue, I will propose HEALTH, as the biggest misnomer literally swallowed day in and day out. Daily pills of polimedication are consumed without question by our whole populations. At the same time, massive media pounding keeps the senses immune to any rational questioning. Where are the journalists who look beyond the tip of their noses?