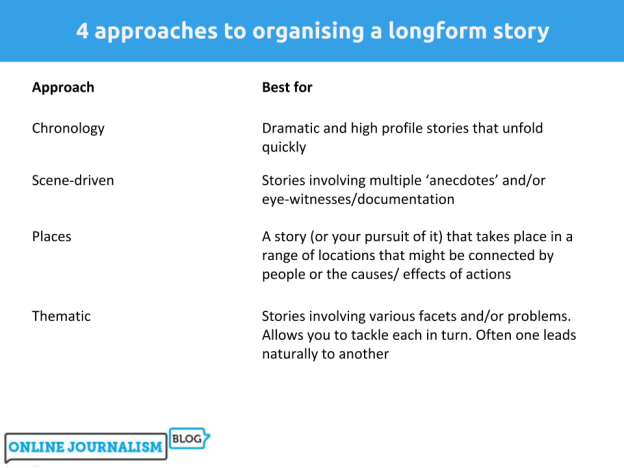

This year on my MA in Data Journalism and MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism I have been teaching students how to plan and organise a longform story. Having already written about story types that can help organise an investigation and beginnings, in this post I want to look at techniques for organising the middle of longform features — and how to wrap it all up at the end.

Middles and endings of long features are no less tricky than the beginnings you can spend so much time writing and rewriting. Often people fall back on particular habits which may not quite ‘work’ for the story being told.

Telling a story in chronological order, for example, is not always the most effective approach. Stories where the action is not equally dispersed chronologically can ‘sag’ in these cases and the momentum of a strong beginning get lost.

In those situations a storyteller with a varied toolbox might use places, or themes, or scenes, to keep that momentum going instead.

Likewise, a lacklustre ending such as “only time will tell” can leave readers feeling deflated or frustrated, however good the story that led up to it. Ensuring you tell the reader what happens next, or what happened to that person you opened the story with (or both) can make a significant impact on an audience’s experience.

In this post I want to spend some time outlining the different ways that journalists approach the ‘middle’ of longform articles — in other words, organising the story into different parts — and how they choose to end those stories strongly.

Middles: organising your story into scenes and chapters

“Chapter Seven” by Jonathan Thorne CC is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Once you’ve started your story, to maintain interest it may help to organise subsequent parts into chapters or ‘scenes’.

How you do this depends on the nature of the story. Here are some suggestions:

Organising stories by chronology

The simplest approach is to organise your story chronologically, and use dates for each chapter, like a diary.

This is quite dry, however: why should I read a chapter titled ‘May 5 2018’?

So it’s best reserved for dramatic and high profile stories that unfold quickly, where you know the reader is already committed.

Organising stories by key ‘scenes’

The Uncatchable tells the picaresque story “of how Greece’s most wanted man became a folk hero” (this is also a rebirth plot).

The chapter titles give a clue to the approach:

- ‘Boy from the mountain’;

- ‘The game changer’ (“a heist more daring than any they had carried out before”);

- ‘Life inside’;

- ‘Inspiration behind bars’;

- ‘On the run’

…and so on. What we have is a series of scenes — chronological, yes, but focused on each story rather than the dates.

Organising a story by place or space

“Map, point” by steelmonkey is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Stories that take place in a variety of settings, especially colourful or glamorous ones, might suit a ‘jetsetting’ approach that takes the reader from place to place.

‘Israel, 1970’, then ‘Moscow, 1990’ for example, makes me immediately curious where this story is going to go next!

Alternatively, you might have a story that breaks down physically into different locations: this is the case with ProPublica’s Cruise Control, which moves from ‘The Kitchen’ to ‘The Pool’, and so on, with a labelled diagram of a ship on the left acting as a navigation tool.

Organising a story by themes (breaking down the problem)

Probably the most common approach involves a story that can be broken down thematically by the different problems you need to solve: in Follow the Money, for example:

- Chapter 1 follows the stories of the players being trafficked;

- Chapter 2 explores the problem of ‘Player trafficking’ as a whole; and

- Chapter 3 is about ‘The complex world of football agents’.

Likewise, in 8000 Holes I broke down the middle of the story into:

- What the sponsors did;

- What LOCOG did; and

- What the rest did

(Before these parts the start sets the scene; and the end rounds it all up).

The Inside Housing feature The rise of the housing activist has a navigation that includes

- ‘Start of a movement’;

- ‘Timeline’;

- ‘Meet the activists’;

- ‘At an occupation’;

- ‘Talking tactics’;

- ‘In the line of fire’ (climax); and

- ‘What next?’ (resolution).

Endings: resolutions and looking forward

“Binocular Boy” by amseaman is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

In news reporting there are two common ways to end a story: with a quote (typically one that sums it all up, or looks ahead), or with a note about what happens next (“The trial continues; a decision is expected”).

A third approach is the ‘response‘ (or lack of), e.g. “The Department for Work and Pensions said they would not comment on individual cases”

The same techniques are often used in longform features, too. Here are some examples:

Congresswoman Matsui and Sen. Blumenthal have advocated making these systems mandatory, calling for the Coast Guard to require all cruise lines to install man-overboard systems on their ships with both an alarm and a video capture feature.

LAPD misclassified nearly 1,200 violent crimes as minor offenses

Officers said it is widely believed that if their division repeatedly fails to meet targets for crime reduction, their chances of being promoted will be seriously harmed.

The department’s focus on numbers has “grown into a dog and pony show, a resource sucker, a cause for fear,” said Patrick Barron, who retired as a detective in 2012 after a 30-year career with the LAPD.

“Detectives should be worried about making sure their cases are thoroughly investigated and their victims and witnesses are treated with dignity,” he said. “They shouldn’t be worried about the statistics.”

I looked around his small living room: the messages on the wall reading “If You Believe In Yourself Anything Is Possible” and “Live Every Moment, Laugh Every Day”, the framed pharmacy certificate among all the family photos, the drugs manuals stacked up by the CD rack. That male mingling of personal with professional pride. Tony had a question.

“How can Boots call itself a healthcare company when it’s done this to me?”

The real estate technique fuelling Vancouver’s housing market

Mr. Love, the Realtor, said that, while much of what’s going on is indicative of a hot market, he thinks it’s tainting his profession.

“It’s a dangerous type of business – you are opening yourself up to all kinds of issues and problems,” Mr. Love said. “They are committing a sin in our business in that we put our clients first.”

Return to the beginning

In some cases the ending returns to the people, places and/or cases introduced early on — any story threads that have been left unresolved are now resolved. In The lawyer who takes the cases no one wants we return to the person who kicks off the story, and some of his cases:

Even Teresa Gudanaviciene had been forced to go another round with the Home Office. Having been given exceptional case funding, she and Giles fought the decision to deport her, and won their case in the first-tier tribunal. The Home Office refused to accept this decision and challenged it in the upper tribunal – which decided that there had in fact been no error of law and that she could stay. “I spoke to her yesterday,” said Giles, when he told me about it. What did she say? “She just said, ‘I don’t know what to say. Thank you.’”

If you are still struggling to think of an ending, try returning to some of the points explore in my post on the 7 types of story — the type of story you are telling may help you identify the type of ending that makes most sense.

Pingback: Longform writing: how to write a beginning to hook the reader | Online Journalism Blog

I think as long as you keep the story interesting the reader will be interested. 😁