Last month I wrote about destination and journey prompts, and the strategy of designing AI prompts to avoid deskilling. In some situations a third, hybrid approach can also be useful. In this post I explain how such hybrid destination-journey prompting works in practice, and where it might be most appropriate.

The industry has a destination habit

The idea of ‘journey’ and ‘destination’ prompts is to distinguish between prompts that develop skills and strategies (the journey), and prompts that focus on a simpler endpoint that saves time by ‘skipping to the end’ (the destination).

Using AI for research, for example, tends to involve a destination prompt that asks for an answer to a question. Summarising large or multiple documents, generating images or other content, lead identification, and translation are other examples.

In other words, the most common applications of large language models (LLMs).

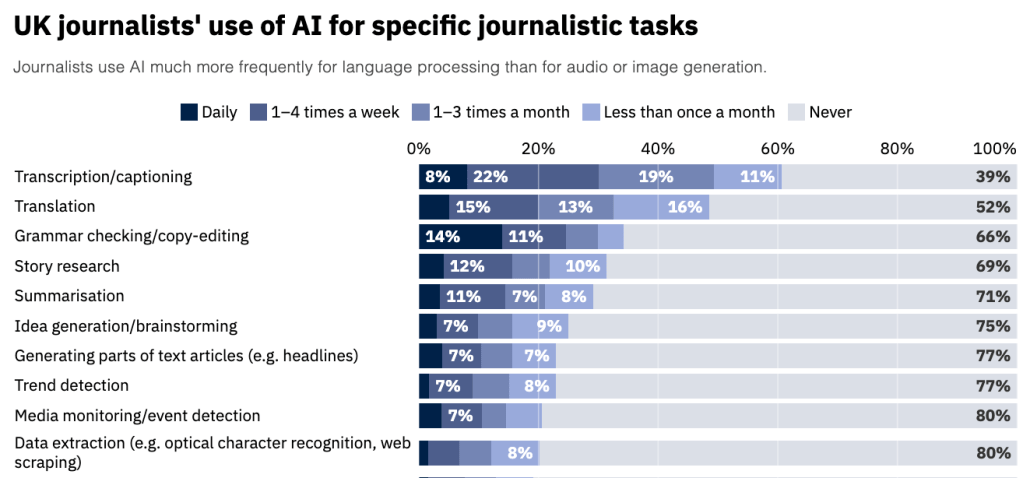

Q: How frequently do you personally work with AI in these journalistic tasks?

Source: AI adoption by UK journalists and their newsrooms: Surveying applications, approaches, and attitudes, published in November 2025.

These applications might appear lazy, but there are various reasons why we might use AI for these tasks:

- Empowerment: It might be the only way we can do that task (e.g. we don’t have budget for a translator or illustrator; we don’t have time to read hundreds of documents)

- Serendipity: It might spot things that we missed (e.g. lead identification alongside our own idea generation)

- Prioritisation: It might free up time for more valuable activity (e.g. drafting content frees up time for research)

- Efficiency: It might be cheaper or easier to use AI than not doing so.

Those are the opportunities — but there are also risks…

The risks of skipping to the end

There are two risks in particular to consider when using a destination prompt: that the quality of the work will be unacceptable (including but not limited to hallucination); and that automating or delegating that work to an LLM will have a negative impact on you or your colleagues, such as deskilling or reduced critical thinking.

When incorporating AI into a workflow, then, it is important to take steps to manage those risks — just as should happen when choosing to delegate similar tasks to an intern, freelancer, or junior member of the team.

Because delegating is precisely what is happening here — and as soon as you begin delegating you become not just a researcher or writer: you become a manager. [UPDATE: Ethan Mollick explores this in depth in his January 27 newsletter on management as an AI superpower]

One Microsoft study describes it as task stewardship: instead of your time being occupied only with research and writing, it now involves commissioning (i.e. designing prompts), answering questions and providing feedback, and selecting, checking and editing the results for quality and accuracy.

A further risk to consider, then, is the simple one of job satisfaction, and where you feel your efforts are most rewarding.

Enter the hybrid destination-journey prompt

Hybrid destination-journey prompting involves augmenting a basic destination prompt with some consideration of your own role in the process. That might be your skills development, critical thinking, or simply steps that might be taken to ‘manage’ the response.

Below is a simple example of a hybrid prompt, which asks a factual question (destination prompting) but adds a question focused on building verification skills (journey prompting).

Who is the head of English at Birmingham City University? Explain how I could verify that information outside of ChatGPT. Regardless of the response, even a very basic hybrid prompt such as this ensures that the user considers the risks involved in using AI, encouraging critical thinking, editorial independence and quality control, and reducing the risk of deskilling.

Here is another example, this time for summarising a document:

I am a journalist doing background research on a story on [topic]. Summarise the document attached. Highlight any points I should verify directly in the source or through additional references. Suggest three questions I should ask myself before relying on this summary in my work.The importance of critical prompt design

If ‘writing an effective commissioning brief’ is a skill we need to develop in managing AI, we should also be designing a more detailed prompt that considers the limitations of the tool we are working with — one that incorporates critical prompt design techniques to manage AI’s tendencies towards sycophancy, greediness and hallucination.

Here is an example of a better designed hybrid prompt which does that:

Is it possible to identify the head of English at Birmingham City University? Explain how confident you are in the response and why. If the answer is uncertain or unverifiable, say so explicitly. Explain how I could verify that information outside of ChatGPT. Once you have answered those questions, do not offer to check any further websites.That prompt adds a number of prompt design techniques:

- An open question rather than a direct order (to reduce the risk of hallucination):

Is it possible to identify - Self-criticism prompting (confidence estimation):

Explain how confident you are in the response - Uncertainty prompting:

If the answer is uncertain or unverifiable, say so explicitly - Negative prompting (to prevent greediness, or scope creep):

do not offer to check any further websites

A prompt summarising a document should be similarly designed to counter-balance the gullibility bias of LLMs

Build enough knowledge to judge the responses

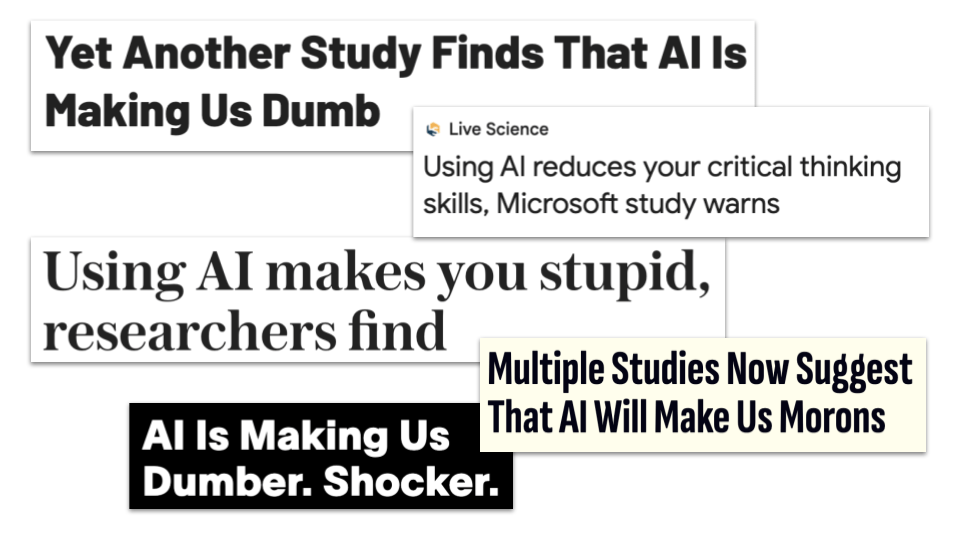

A growing body of research on the impact of AI usage on critical thinking suggests that AI usage can have a negative impact unless we have, or build, crucial subject knowledge and an awareness of AI’s flaws.

One (frequently misquoted) Microsoft study identifies two key factors that shape critical thinking (defined as including “analysis, synthesis, and evaluation”): a person’s confidence in AI, and their confidence in performing the task that they are asking the AI to perform.

If a person has high confidence in their own ability to perform a task, and low confidence in AI’s ability, they are likely to use more critical thinking in the task

But if a person has low confidence in their own ability to perform a task, and high confidence in AI, they are likely to use less critical thinking.

The takeaway is clear: we should ideally build knowledge and experience of a task ourself before asking AI to perform it.

If that is not possible, we should be especially rigorous in finding out and understanding what qualities are important in assessing the results of such tasks.

Either way, we should also be conscious that AI suffers from a number of flaws when performing tasks which will need to be checked for.

There are no shortcuts

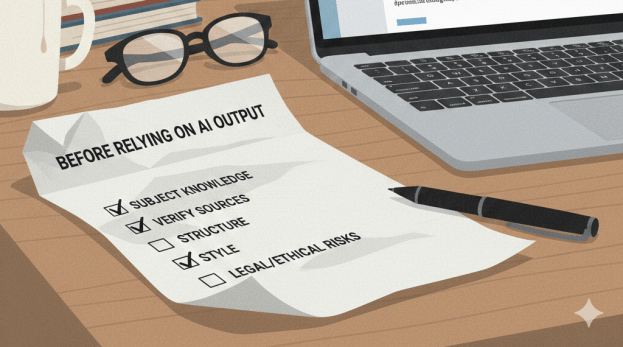

For example, if we were asking an LLM to draft a news article we should really have experience of writing enough news articles ourselves to be confident of judging the results.

If we don’t then we have the responsibility to at least understand certain things to judge it effectively: the principles of news article structure, grammar and spelling, law and ethics (e.g. accuracy, objectivity), and the style requirements of the target publication are just some that we might list. We might also seek help from someone who does have the experience we lack.

If we don’t have experience or knowledge in an area, use of AI is particularly high risk because we have no way of judging whether it has produced something usable or not, regardless of how impressive it seems (if lawyers repeatedly fall for it, so will you).

Even with experience and knowledge, you will also need to bear in mind AI’s key weaknesses:

- AI’s verbosity leads to a tendency to overwrite;

- Hallucination creates issues around accuracy;

- The training of LLMs on a range of material outside of your context means they are likely to suffer from flaws in style that will need significant adaptation for your country, industry, and target publication.

An MIT study adds another consideration: if we use a muscle more, it becomes stronger; but if we use it less, it becomes weaker.

So, the more we spend our time on new ‘muscles’ like prompt design, interviewing and verification, the stronger those ‘muscles’ should become — but using AI costs us the opportunity to develop other muscles, whether that’s research, summarisation, or writing.

That balance between an opportunity and a cost is something to consider carefully, and a risk to manage too.

Agree with this framing. Hybrid prompts help preserve verification and critical thinking while still benefiting from automation.