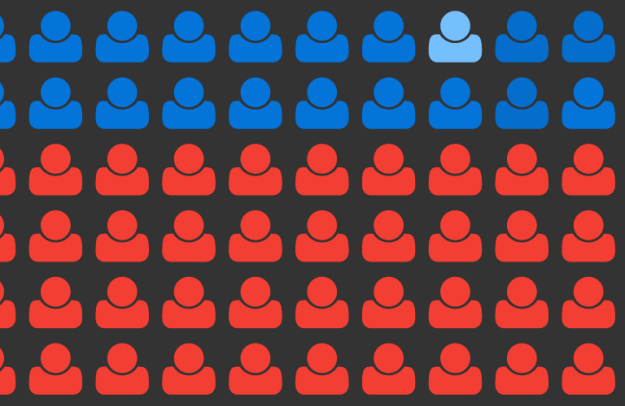

In the Bureau’s Naming the Dead visualisation, blue indicates civilian victims and red alleged militants

Giving a voice to the voiceless is one of the core principles of journalism. Traditionally this means those without the power or money to amplify their own voices, but in recent years a strand of work has developed in data journalism that deserves particular attention: projects which give a voice to people who literally don’t have one — because they are dead.

The nameless dead

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism‘s Naming the Dead project has been one of the earliest and most persistent: tracking and investigating US covert drone strikes since 2011 and seeking to identify those killed.

It is a simple idea, and one that requires no ‘data’ skills: in fact the only act of ‘data journalism’ involved is to convert unstructured and distributed reports from a variety of sources into one structured dataset. The rest is legwork and persistence.

But that simple act can have a massive impact:

“[It] has helped to inform the public debate both around the use of drones in Pakistan and about the emergence of the unmanned aircraft as a weapon of war. Our data has been used in academic studies, campaigns, new media projects and scores of press reports. Our investigations have been cited by UN special rapporteurs, the New York Times and campaign groups such as the American Civil Liberties Unit (ACLU) and Amnesty International.”

15,000 extra civilian deaths

A year earlier the Bureau had been involved in the analysis of the Iraq war logs, a story about the voiceless on a different scale: the logs revealed at least 15,000 previously unreported civilian deaths, a figure which itself may be underreported.

The Guardian mapped every death from the Iraq war logs

Seeing those deaths (and non-civilian deaths) mapped by The Guardian helped show the sheer scale of the tragedy. But as I wrote in One ambassador’s embarrassment is a tragedy, 15,000 civilian deaths is a statistic, it presented problems in terms of making a human connection.

A voice on mobile

In 2014 the Trinity Mirror data project Ampp3d tackled that problem by putting 1,200 dead construction workers into ‘teams’ to mirror the World Cup they were working on.

It was designed to have an impact on mobile. And as I wrote at the time:

“The result is percussive: 23 players, 23 dead workers; 23 players, 23 dead workers: 23. 23. 23. 23.

“By the time we reach the USA team, after 32 repetitions of this pattern, we are punch drunk. Then comes the knockout.

“… It’s the physicality of the experience which is fascinating: moving your finger or thumb down and down and down as you try to reach the end of these deaths. Just try it: view this on a mobile phone now.”

The Migrants Files

Deaths can have a key impact on policy too: in 2013 The Migrants Files launched in an attempt to do  something similar to Naming The Dead: this time giving a coherence to the various reports of emigrants who died as they attempted to reach Europe.

something similar to Naming The Dead: this time giving a coherence to the various reports of emigrants who died as they attempted to reach Europe.

Like Naming The Dead, the team made the data public so others could interrogate and use it. They also built the platform Detective.io to make it easier for others to collaborate on similar large scale data-curation projects.

Gun deaths

And now The Guardian’s The Counted seeks to document people killed by police in the US this year where no records are kept:

“The US government has no comprehensive record of the number of people killed by law enforcement. This lack of basic data has been glaring amid the protests, riots and worldwide debate set in motion by the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old, in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014.”

Data journalism that makes data for journalism

Too often data journalism is described in ways that focus on the technical act of working with existing data. But to be voiceless often means that no data exists about your experience.

It can mean that you are literally not counted.

When data lies at the heart of most modern decision-making, collecting or curating the data about those experiences can be one of the most important acts of data journalism there is.

It is the least technically demanding type of data journalism, too, laying the foundations for other, more technically skilled journalists, developers and designers to do further work.

All you have to do is start counting…

Pingback: Giving a voice to the (literally) voiceless: data journalism and the dead | Online Journalism Blog | do not drop the ball

That´s what we tried to do in this project… http://interactivo.eluniversal.com.mx/muertos-sinnombre/

Pingback: 10 principles for data journalism in its second decade | Online Journalism Blog

Pingback: 3 more angles most often used to tell data stories: explorers, relationships and bad data stories | Online Journalism Blog

Pingback: 3 more angles most often used to tell data stories: explorers, relationships and bad data stories – Media