Image from jonnycampbell.com

Various parts of the media were hoaxed this week by Belfast student Jonny Campbell’s claim to have won a Twitter internship with Charlie Sheen. The hoax was well planned, and to be fair to the journalists, they did chase up documentation to confirm it. Where they made mistakes provides a good lesson in online verification.

Where did the journalist go wrong? They asked for the emails confirming the internship, but accepted a screengrab. This turned out to be photoshopped.

They then asked for further emails from earlier in the process, and he sent those (which were genuine) on.

They should have asked the source to forward the original email.

Of course, he could have faked that pretty easily as well (I’m not going to say how here), so you would need to check the IP address of the email against that of the company it was supposed to be from.

An IP address is basically the location of a computer (server). This may be owned by the ISP you are using, or the company which employs you and provides your computer and internet access.

This post explains how to find IP addresses in an email using email clients including Gmail, Yahoo! Mail and Outlook – and then how to track the IP address to a particular location.

This website will find out the IP address for a particular website – the IP address for Internships.com is 204.74.99.100, for example. So you’re looking for a match (assuming the same server is used for mail). You could also check other emails from that company to other people, or ideally to yourself (Watch out for fake websites as well, of course).

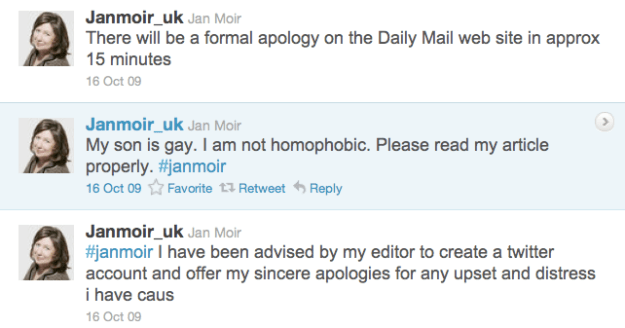

And of course, finally, it’s always worth looking at the content the hoaxer has provided and clues that they may have left in it – as Jonny did (see image, left).

For more on verifying online information see Content, context and code: verifying information online, which I’ll continue to update with examples.