Continuing the serialisation of the research underpinning a new Help Me Investigate project, in this third part I describe how the focus of the site was shaped by the interests of its users and staff, and how site functionality was changed to react to user needs. I also identify some areas where the site could have been further developed and improved. (Part 1 is available here; Part 2 is here)

Reflections on the proof of concept phase

By the end of the 12 week proof of concept phase the site had also completed a number of investigations that were not ‘headline-makers’ but fulfilled the objective of informing users: in particular ‘Why is a new bus company allowed on an existing route with same number, but higher prices?’; ‘What is the tracking process for petitions handed in to Birmingham City Council?’ and ‘The DVLA and misrepresented number plates’

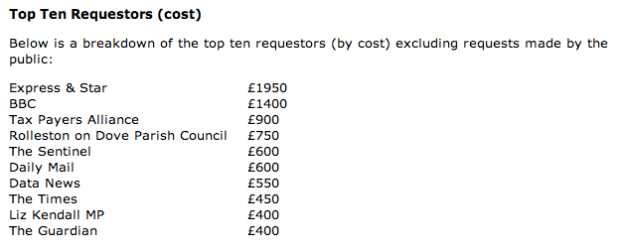

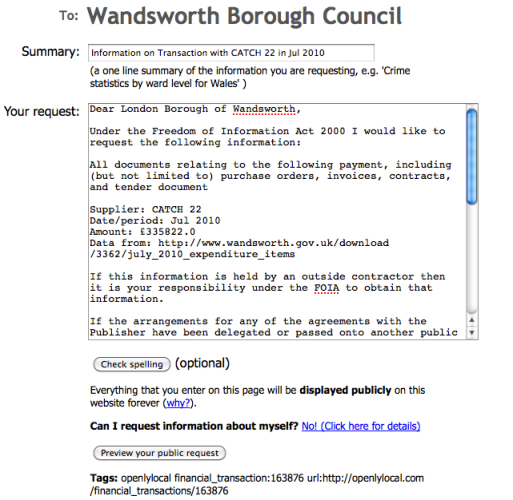

The site had also unearthed some promising information that could provide the basis for more stories, such as Birmingham City Council receiving over £160,000 in payments for vehicle removals; and ‘Which councils in the UK (that use Civil Enforcement) make the most from parking tickets?’ (as a byproduct, this also unearthed how well different councils responded to Freedom of Information requests#)

A number of news organisations expressed an interest in working with the site, but practical contributions to the site took place largely at an individual rather than organisational level. Journalist Tom Scotney, who was involved in one of the investigations, commented: “Get it right and you’re becoming part of an investigative team that’s bigger, more diverse and more skilled than any newsroom could ever be” (Scotney, 2009, n.p.) – but it was becoming clear that most journalists were not culturally prepared – or had the time – to engage with the site unless there was a story ‘ready made’ for them to use. Once there were stories to be had, however, they contributed a valuable role in writing those stories up, obtaining official reactions, and spreading visibility.

After 12 weeks the site had around 275 users (whose backgrounds ranged from journalism and web development to locally active citizens) and 71 investigations, exceeding project targets. It is difficult to measure ‘success’ or ‘failure’ but at least eight investigations had resulted in coherent stories, representing a success rate of at least 11%: the target figure before launch had been 1-5%. That figure rose to around 21% if other promising investigations were included, and the sample included recently initiated investigations which were yet to get off the ground.

‘Success’ was an interesting metric which deserves further elaboration. In his reflection on The Guardian’s crowdsourcing experiment, for example, developer Martin Belam (2011a, n.p.) noted a tendency to evaluate success “not purely editorially, but with a technology mindset in terms of the ‘100% – Achievement unlocked!’ games mechanic.”. In other words, success might be measured in terms of degrees of ‘completion’ rather than results.

In contrast, the newspaper’s journalist Paul Lewis saw success in terms of something other than pure percentages: getting 27,000 people to look at expense claims was, he felt, a successful outcome, regardless of the percentage of claims that those represented. And BBC Special Reports Editor Bella Hurrell – who oversaw a similar but less ambitious crowdsourcing project on the same subject on the broadcaster’s website, felt that they had also succeeded in genuine ‘public service journalism’ in the process (personal interview).

A third measure of success is noted by Belam – that of implementation and iteration (being able to improve the service based on how it is used):

“It demonstrated that as a team our tech guys could, in the space of around a week, get an application deployed into the cloud but appear integrated into our site, using a technology stack that was not our regular infrastructure.

“Secondly, it showed that as a business we could bring people together from editorial, design, technology and QA to deliver a rapid turnaround project in a multi-disciplinary way, based on a topical news story.

“And thirdly, we learned from and improved upon it.“ (Belam, 2010, n.p.)

A percentage ‘success’ rate of Help Me Investigate, then, represents a similar, ‘game-oriented’ perspective on the site, and it is important to draw on other frameworks to measure its success.

For example, it was clear that the site did very well in producing raw material for ‘journalism’, but it was less successful in generating more general civic information such as how to find out who owned a piece of land. Returning to the ideas of Actor-Network Theory outlined above, the behaviour of two principal actors – and one investigation – had a particular influence on this, and how the site more generally developed over time. Site user Neil Houston was an early adopter of the site and one of its heaviest contributors. His interest in interrogating data helped shape the path of many of the site’s most active investigations, which in turn set the editorial ‘tone’ of the site. This attracted users with similar interests to Neil, but may have discouraged others who did not – further research would be needed to establish this.

Likewise, while Birmingham City Council staff contributed to the site in its earliest days, when the council became the subject of an investigation staff’s involvement was actively discouraged (personal interview with contributor). This left the site short of particular expertise in answering civic questions.

At least one user commented that the site was very ‘FOI [Freedom Of Information request]-heavy’ and risked excluding users interested in different types of investigations, or who saw Freedom of Information requests as too difficult for them. This could be traced directly to the appointment of Heather Brooke as the site’s support journalist. Heather is a leading Freedom of Information activist and user of FOI requests: this was an enormous strength in supporting relevant investigations but it should also be recognised how that served to set the editorial tone of the site.

This narrowing of tone was addressed by bringing in a second support journalist with a consumer background: Colin Meek. There was also a strategic shift in community management which involved actively involving users with other investigations. As more users came onto the site these broadened into consumer, property and legal areas.

However, a further ‘actor’ then came into play: the legal and insurance systems. Due to the end of proof of concept funding and the associated legal insurance the team had to close investigations unrelated to the public sector as they left the site most vulnerable legally.

A final example of Actor-Network Theory in action was a difference between the intentions of the site designers and its users. The founders wanted Help Me Investigate to be a place for consensus, not discussion, but it was quickly apparent users did not want to have to go elsewhere to have their discussions. Users needed to – and did – have conversations around the updates that they posted.

The initial challenge-and-result model (breaking investigations down into challenges with entry fields for the subsequent results, which were required to include a link to the source of their information) was therefore changed very early on to challenge-and-update: people could now update without a link, simply to make a point about a previous result, or to explain their efforts in failing to obtain a result.

One of the challenges least likely to be accepted by users was to ‘Write the story up’. It seemed that those who knew the investigation had no need to write it up: the story existed in their heads. Instead it was either site staff or professional journalists who would normally write up the results. Similarly, when an investigation was complete, it required site staff to update the investigation description to include a link to any write-up. There was no evidence of a desire from users to ‘be a journalist’. Indeed, the overriding objective appeared rather to ‘be a citizen’.

In contrast, a challenge to write ‘the story so far’ seemed more appealing in investigations that had gathered data but no resolution as yet. The site founders underestimated the need for narrative in designing a site that allowed users to join investigations while they were in progress.

As was to be expected with a ‘proof of concept’ site (one testing whether an idea could work), there were a number of areas of frustration in the limitations of the site – and identification of areas of opportunity. When looking to crowdfund small amounts for an investigation, for example, there were no third party tools available that would allow this without going through a nonprofit organisation. And when an investigation involved a large crowdsourcing operation the connection to activity conducted on other platforms needed to be stronger so users could more easily see what needed doing (e.g. a live feed of changes to a Google spreadsheet, or documents bookmarked using Delicious).

Finally investigations often evolved into new questions but had to stay with an old title or risk losing the team and resources that had been built up. The option to ‘export’ an investigation team and resources into a fresh question/investigation was one possible future solution.

‘Failure for free’ was part of the design of the site in order to allow investigations to succeed on the efforts of its members rather than as a result of any top-down editorial agenda – although naturally journalist users would concentrate their efforts on the most newsworthy investigations. In practice it was hard to ‘let failure happen’, especially when almost all investigations had some public interest value.

Although the failure itself was not an issue (and indeed the failure rate lower than expected), a ‘safety net’ was needed that would more proactively suggest ways investigators could make their investigation a success, including features such as investigation ‘mentors’ who could pass on their experience; ‘expiry dates’ on challenges with reminders; improved ability to find other investigators with relevant skills or experience; a ‘sandbox’ investigation for new users to find their feet; and developing a metric to identify successful and failing investigations.

Communication was central to successful investigations and two areas required more attention: staff time in pursuing communication with users; and technical infrastructure to automate and facilitate communication (such as alerts to new updates or the ability to mail all investigation members)

The much-feared legal issues threatened by the site did not particularly materialise. Out of over 70 investigations in the first 12 weeks, only four needed rephrasing to avoid being potentially libellous. Two involved minor tweaks; the other two were more significant, partly because of a related need for clarity in the question.

Individual updates within investigations, which were post-moderated, presented even less of a legal problem. Only two updates were referred for legal advice, and only one of those rephrased. One was flagged and removed because it was ‘flamey’ and did not contribute to the investigation.

There was a lack of involvement by users across investigations. Users tended to stick to their own investigation and the idea of ‘helping another so they help you’ did not take root. Further research is needed to see if there was a power law distribution at work here – often seen on the internet – of a few people being involved in lots of investigations, most being involved in one, and a steep upward curve between.

In the next part I look at one particular investigation in an attempt to identify the qualities that made it successful.

If you want to get involved in the latest Help Me Investigate project, get in touch on paul@helpmeinvestigate.com