Too often discussion around using AI is “either/or” — an assumption that you either use AI for a task, or do it yourself. But there’s another option: do both.

“Parallel prompting“* is the term I use for this: while you perform a task manually, you also get the AI to perform the same task algorithmically.

For example, you might brainstorm ideas for a story while asking ChatGPT to do the same. Or you might look for potential leads in a company report — and upload it to NotebookLM to perform the same task. You might draft an FOI request but get Claude to draft one too, or get Copilot to rewrite the intro to a story while you attempt the same thing.

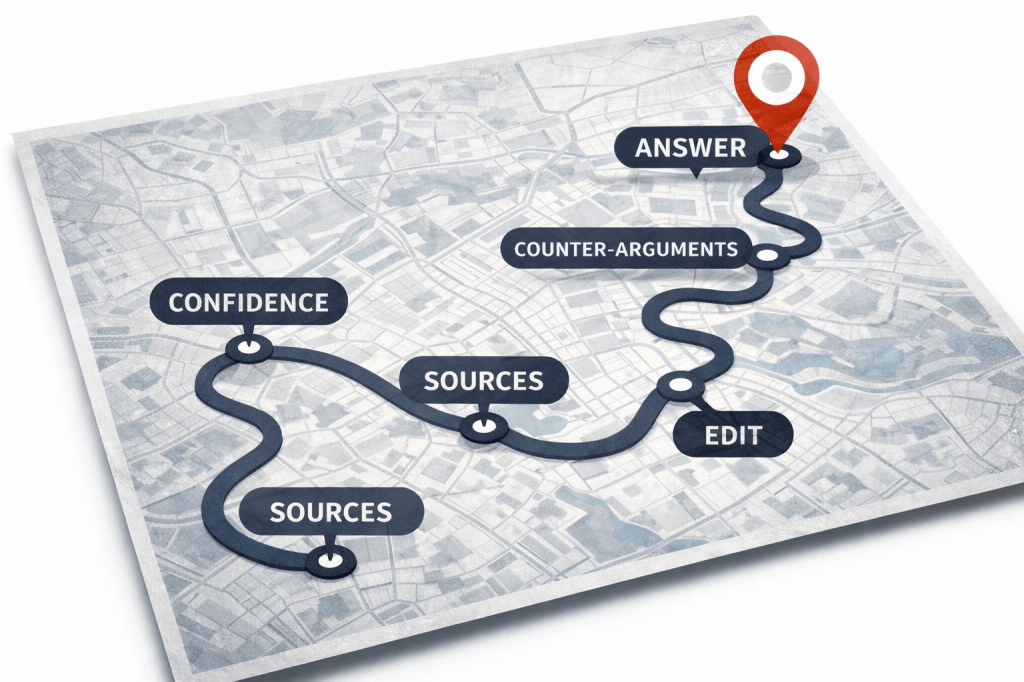

Then you compare the results.

Continue reading