Liveblogging exercise trending on Twitter

In the final part of a trilogy of articles on liveblogging I wanted to talk about a recent experiment I conducted in teaching liveblogging, where I decided to abandon most of my planned lecture on the topic and stage a live ‘event’ instead.

I’d also like to this post to provide a space to share your own experiences of teaching liveblogging and mobile journalism.

One of the biggest problems in teaching liveblogging – and of much of online journalism in fact – is getting students to ‘unlearn’ assumptions about journalism production learned in an analogue context. You can talk about the need to operate across a network, to multitask and to look for where the need lies – but there’s nothing like experience to drill that home.

Casting the panel: image by @mattclinch81

The event

I decided to recreate one of the less interesting events to liveblog: a committee hearing. I could have chosen to recreate a demonstration or a riot, but aside from the obvious potential for things to go horribly wrong, recreating something less ‘eventful’ meant I could communicate some important lessons about those sorts of events – more on which below.

Specifically, I took the transcript from one of the committee hearings into the MPs’ expenses scandal in the UK. Specifically, I chose the evidence of a husband and wife, providing as it did a little extra colour.

Image by @andrewstuart

Precautions

Because the event was going to be tweeted live and in public, I had to make sure that there was no chance of libel. And so the names of all participants were changed to quite obviously false ones: the MP was Alan Fiction (Fiction, Al – see what I did there?) and the various committee members had names that made them sound like Mr Men characters (“Dr Fashionabletrousers”).

Normally hashtags emerge organically but I decided to specify a hashtag up front to make the nature of the event explicit, and so #FAKEevent was born.

With those precautions in place I needed to give the event some dynamics that would show the students the issues they would have to deal with in a live situation. Specifically: multiple sources of information; unexpected events; and incomplete information.

Image by @iamdjcarlo

The roles

The room (over 200 students) was split into 4 main groups: over half made up a group playing the role of journalists. These were asked to move so that they were all sat in the central column of seats. To further mix things up, I gave them different editorial contexts: one quarter was working for a left-leaning broadsheet; another for a right-leaning one; a third quarter was working for a public broadcaster; and a final one for a commercial broadcaster.

20 more students each made up a pro-MP group, and an anti-MP group, who occupied the left and right columns of seats respectively. A final group of 10 or so students were ‘bystanders‘, occupying the back row.

In addition, a group of 10 or so took the roles of the committee itself, the MP and his ‘wife’.

These groups were now given the following materials:

- The committee/MP/wife: an edited transcript of the hearing which they were to use as a script. Also: instructions for particular actions that individuals should do at specific times (more below)

- The journalists: briefing notes: the members of the panel; background on the MP

- Pro-MP group: instructions that they should try to steer coverage in a positive direction, and details of the website that they could use to do so.

- Anti-MP group: instructions that they should try to steer coverage in a negative direction, and details of the website that they could use to do so.

- The bystanders: instructions on who they were, and the roles they would play (more below).

I had also approached 3 students beforehand to play specific roles within those groups: one student each as the ‘editor’ of the pro- and anti-MP websites, who had already been assigned admin access to their particular blog and so could give other students publishing rights; and a third student who would act as the major ‘disruption’ to the event.

And I had told all students ahead of the event to bring either a laptop or mobile phone from which they could publish to the web.

A series of unfortunate events

The transcript formed the backdrop to a number of other events which I wanted to use as a device for demonstrating the skills they would need as livebloggers:

- One member of the panel would begin to fall asleep after a minute. This was to test how many were only paying attention to the testimony.

- Another member would shout ‘Snake!’ after 2 minutes, waking the first person up. Again, who would be paying attention? Would they have made a note of who he was?

- A third member would stare intently at the wife throughout – a small detail; who would notice?

- After 5 minutes or so, my ‘plant’ would storm into the back of the room and shout a loud accusation at the MP, then be calmly escorted out. Most journalists would not have seen what happened (because it was behind them), and so would have to reconstruct events from the bystanders in the back row, some of whom had their own agendas and some of whom had recorded it.

In all, the exercise took some time to organise (here are my notes): around 20-25 minutes to get everyone into their groups and around 7 minutes for the event itself (actually longer as my interruption held back for some time, waiting for a nod). A livestream of tweets (using Twitterfall) was put up on the projector – if you had a phone set up with Qik or Bambuser you could also stream the video.

image of sleeping panel member by @nicky_henderson

The lessons

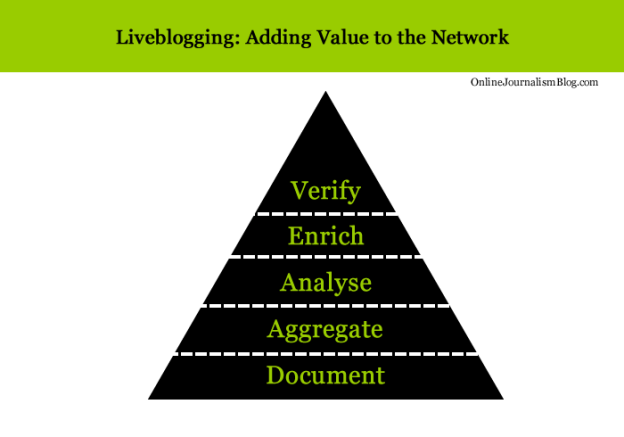

Choosing a staged event like a committee hearing that wasn’t particularly eventful meant that the students had to do a number of things over and above reacting to events.

Firstly, they had to concentrate on what was taking place because it was easy to lose concentration when nothing interesting was happening.

Secondly, they had to make things interesting. Many resorted to opinion and wit – entertaining, but not particularly informative, although that was excusable given that the event and the actors were fictional, and there was no background knowledge (other than that in the briefing notes) to draw on.

Still, the point wasn’t what they did but rather what they learned, and the frustrations of needing that background were a useful teaching tool in themselves.

Finally, they had to be proactive: seek out information, find out what had happened.

At the end of the exercise I asked them what they had learned, and pointed out some things I’d noticed myself about how they’d dealt with the challenge:

- Some noted the difficulties of taking in information from both the event itself and on Twitter. This is a skill that comes from practice – or if you have the resources, partnering up with another journalist.

- Not a single student got up from their seat and moved – either to hear the proceedings more clearly (at least one tweeted that they couldn’t hear what was being said) or to speak to the bystanders

- Only one found out the name of the protestor. None picked up on his hashtagged tweets. None traced his blog where his accusations were fleshed out.

- Most journalists did not follow what was being said about the event, and put it into context

- Few took images or other multimedia

Once again: the point wasn’t that they do things right; in many ways they were set up to fail, and the discussion at the end was about reflecting on those rather than playing a blame game.

‘Failure’ was used as a teaching tool: instead of telling them what they should do, expecting them to remember, and giving them an exercise to do that, I wanted to give them an exercise up front, to experience and internalise that desire to do better, and use that as the context for the lessons, so they could connect it to their own experience of liveblogging rather than experiences of, for example, live broadcast or print reporting. (It seemed to work – a couple of students took the time to express their thanks for the nature of the lesson.)

So although that left me much less time to pass on a lesson, it did, I hope, leave the students learning more and with a higher motivation to continue learning (the full presentation, by the way, was available for those who wanted to go through it).

On the motivation side, the hashtag for the event also trended not only in the UK but in the US too, which I think the students rather enjoyed.