I’ve tweeted a couple of times recently about frustrations with BBC stories that are based on data but treat it poorly. As any journalist knows, two occasions of anything in close proximity warrants an overreaction about a “worrying trend”. So here it is.

“One in four council homes fails ‘Decent Homes Standard'”

This is a good piece of newsgathering, but a frustrating piece of online journalism. “Almost 100,000 local authority dwellings have not reached the government’s Decent Homes Standard,” it explained. But according to what? Who? “Government figures seen by BBC London”. Ah, right. Any chance of us seeing those too? No.

The article is scattered with statistics from these figures “In Havering, east London, 56% of properties do not reach Decent Homes Standard – the highest figure for any local authority in the UK … In Tower Hamlets the figure is 55%.”

It’s a great story – if you live in those two local authorities. But it’s a classic example of narrowing a story to fit the space available. This story-centric approach serves readers in those locations, and readers who may be titillated by the fact that someone must always finish bottom in a chart – but the majority of readers will not live in those areas, and will want to know what the figures are for their own area. The article does nothing to help them do this. There are only 3 links, and none of them are deep links: they go to the homepages for Havering Council, Tower Hamlets Council, and the Department of Communities and Local Government.

In the world of print and broadcast, narrowing a story to fit space was a regrettable limitation of the medium; in the online world, linking to your sources is a fundamental quality of the medium. Not doing so looks either ignorant or arrogant.

“Uneven progress of UN Millennium Development Goals”

An impressive piece of data journalism that deserves credit, this looks at the UN’s goals and how close they are to being achieved, based on a raft of stats, which are presented in bar chart after bar chart (see image above). Each chart gives the source of the data, which is good to see. However, that source is simply given as “UN”: there is no link either on the charts or in the article (there are 2 links at the end of the piece – one to the UN Development Programme and the other to the official UN Millennium Development Goals website).

This lack of a link to the specific source of the data raises a number of questions: did the journalist or journalists (in both of these stories there is no byline) find the data themselves, or was it simply presented to them? What is it based on? What was the methodology?

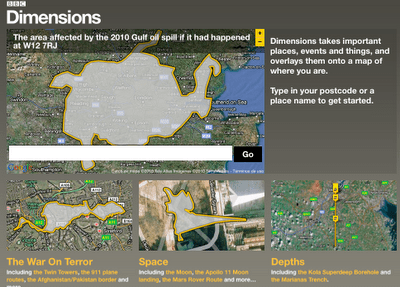

The real missed opportunity here, however, is around visualisation. The relentless onslaught on bar charts makes this feel like a UN report itself, and leaves a dry subject still looking dry. This needed more thought.

Off the top of my head, one option might have been an overarching visualisation of how funding shortfalls overall differ between different parts of the world (allowing you to see that, for example, South America is coming off worst). This ‘big picture’ would then draw in people to look at the detail behind it (with an opportunity for interactivity).

Had they published a link to the data someone else might have done this – and other visualisations – for them. I would have liked to try it myself, in fact.

UPDATE: After reading this post, a link has now been posted to the report (PDF).

Compare this article, for example, with the Guardian Datablog’s treatment of the coalition agreement: a harder set of goals to measure, and they’ve had to compile the data themselves. But they’re transparent about the methodology (it’s subjective) and the data is there in full for others to play with.

It’s another dry subject matter, but The Guardian have made it a social object.

No excuses

The BBC is not a print outlet, so it does not have the excuse of these stories being written for print (although I will assume they were researched with broadcast as the primary outlet in mind).

It should also, in theory, be well resourced for data journalism. Martin Rosenbaum, for example, is a pioneer in the field, and the team behind the BBC website’s Special Reports section does some world class work. The corporation was one of the first in the world to experiment with open innovation with Backstage, and runs a DataArt blog too. But the core newsgathering operation is missing some basic opportunities for good data journalism practice.

In fact, it’s missing just one basic opportunity: link to your data. It’s as simple as that.

On a related note, the BBC Trust wants your opinions on science reporting. On this subject, David Colquhoun raises many of the same issues: absence of links to sources, and anonymity of reporters. This is clearly more a cultural issue than a technical one.

Of all the UK’s news organisations, the BBC should be at the forefront of transparency and openness in journalism online. Thinking politically, allowing users to access the data they have spent public money to acquire also strengthens their ideological hand in the Big Society bunfight.

UPDATE: Credit where it’s due: the website for tonight’s Panorama on public pay includes a link to the full data.